Excerpted from A Whirld of Words: A Reader's Commonplace Dictionary, and looking for a publisher. This dictionary tells a story of a long life of reading and intellectual curiosity. Whirld abounds in select quotations with wit, character, and scope, pith and pluck and dash. It is particularly bookish, metaphysical, and ironic. Robust in history, poetry, and philosophy, it is a book about books, and an antidote to book madness (bibliomania). It is a tool for thinking, but its aim is above all to delight!

Here is the Introduction to, A Whirld of Words.

O Redre

You are the wonder of our universe. What you are doing right now is a marvel, beyond all others. The print on the page you are reading conveys vast amounts of information from minute observations as your eye saccades across the lines of letters and symbols. The print on the page is a mechanical marvel, more than any single thing, what made the world modern. But, still, the greater marvel is you. Because you have to inhabit, occupy, and inform the print on the page to give it life. The white space, and even the print, is just vasty void without you. None of what you see on the page has meaning until you put yourself into the space and invest yourself in the text. A reader requires blank space like a fish requires water.

Look now at all the white space on this page – not just the margins, but the intimate space between the words and letters, and within them, that give definition to the contrasting ink that appears. There you are, informing that space, these spaces. Linking everything together. The reader is in the white space, coursing through the flurry of symbols, making connections, predictions, associations, judgments. Minds meet in the white space.

Thank you for joining the discourse. Welcome to my Whirld. There is plenty of space for you here.

A Reading Life

The purpose of this book is to round out the story of my life. It deals with books as vital experience.

This dictionary tells a story, a reader’s story. It reflects a life of intellectual curiosity. My vocation for more than sixty years has been thinking, reading, and writing. I have always had a lust for great ideas, learned work, and superlative writing. I only regret that I could not read every such thing.

My hobbies have included the practice of law, software entrepreneurship, and rare book dealing. I was an advocate, a trial and a transactional lawyer, helping people defend life and liberty, get out of jams, do deals, form companies, and develop, protect and exploit intellectual property. I was counsel to top Bay Area software companies. I was a founder, chairman, and chief executive officer of Webcorp, where we developed a peer-to-peer network operating system trademarked as ‘Web’, purchased by Microsoft. Yes, I became a rare book dealer when bookstores became scarce and librarians dumped books in trash bins by the ton. But these were, in retrospect, hobbies, curiosities, exposures. Mine was an unconventional career, directed more by the curiosity I mentioned than by the ambition you might expect. The main show has always been thinking, reading, and writing.

My undergraduate experience had many high points and some superb mentorship. I studied Latin and Homeric Greek with a logomaniac. I was the catalyst for a Shakespeare scholar to get Hill Foundation funding for an elaborate undergraduate tutorial program. My medievalist principal tutor was elected president of the University before we began; for my last four semesters, Wednesday afternoons in his office getting grilled, was exhilarating. The Honors Program there began with a sophomore year focused on the history and philosophy of science, followed by two years with a ‘great books in paperback’ regimen. In a meeting as sophomores before the summer break, we were handed a staggering reading list and told we were expected to buy the books promptly and read them with dispatch on our own initiative over the next two years. Two things were conspicuously chalked on the blackboard:

life ≠ work

life is opaque on all levels

Told the course would begin in the Fall with a focus on the sublime, we should at least read The Brothers Karamazov in the summer in preparation. That, of course, left dozens of other sublime titles on the list to account for. Hobbes, Rousseau and Nietzsche would follow in class and finish out junior year. As seniors, we would study and discuss Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, and Tolstoy’s War and Peace. A thrill set in, tinged with terror, followed by a trip to the bookstore.

The Honors Seminar was, in a way, a precursor of this Whirld. We were a small group at a big table in a lofty room at the remote top of a massive brick quadrangle, meeting two nights a week from seven to nine. The master was a monk, a refugee from Korea, forever mum about all that, who studied at the Committee for Social Thought at the University of Chicago. He had a fertile mind, and somehow had already read everything. He got personal friends and acquaintances like Saul Bellow, Hannah Arendt, David Grene, and Wystan Auden to visit the campus, and give a public lecture and a private seminar for the honors students.

Regularly, though not exclusively, he read pertinent excerpts to us from dozens of thinkers and critics on the subjects and texts he put under discussion. I said he read, when I should have said, he dictated. He made us copy these out as he read in spurts. He would read a bit, and watch us write in small chops, while he sipped water from a paper cup. Every dullard had to do it, and would be taught something in spite of indolent attitudes. He typed more excerpts, all week long, for the bonus handouts we also got during every class. These notebooks and handouts remain a treasured archive. Sounds primitive as pedagogy, but it worked to great effect. He made us create commonplace books. I suppose it should be considered a model for the methodology I employed in putting this dictionary together.

I went to graduate school at the University of Toronto, and was a student at both the Centre for Medieval Studies and the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (O, orthography!). Though I did not acquire the lettertrumpets of the PIMS Licentiate, it is from that time that I book the authority and investiture of my perpetual, worldwide, unrestricted license to pontificate. I employ it proudly and liberally.

My wonder at excellence in scholarship is akin to the thrills of a seven-year-old watching the aerial acrobatics above the three rings of Barnum and Bailey. An arabesque of learning, skill, discipline and accuracy. I studied the Later Roman Empire with an eminent historian with a Balliol, Queens, pedigree, a Ronald Syme protégé. The curriculum at the Institute was broad and rigorous, including medieval canon law with the preeminent palaeographer who would be the next Prefect of the Vatican Library; vernacular medieval literatures with a consummate English philologist who castigated and denounced Oxford for its misappropriation of the New English Dictionary, at every opportunity; and study of ancient and medieval mosaics with a distinguished European scholar who spent her summers ascending the scaffolding inside Hagia Sophia to study tesserae, and suchlike.

The prosopography of the Institute and those I encountered as a graduate student would require considerable comedic talent to render adequate portraits. There is character, and there are characters. The character of the experience was indelible. Suffice it to say it was all most memorable and stimulated a lifetime of learning. Whirld displays an unabashed love of scholars and scholarship that derives from these early learning experiences.

Reading

My heavenly patron, Jerome, said, ‘Read everything; keep what is good’. Whirld retains what a prodigious, voracious, reader found to be defining. In like fashion, a well-known dictum of Hugh of St. Victor inspired Leonard Boyle, that Prefect of the Vatican Library: 'Learn everything. Afterwards you will find that nothing is superfluous' (Omnia disce. Postea videbis nichil esse superfluum). These maxims speak to the genesis, ambition and scope of Whirld.

We earnestly assert with Montaigne that books are the best provision to be found for this human journey. And even in an electronic age of instant communication, one can still be allowed to believe that books as a form for expression will persist and prevail when it comes to price, portability, and random access.

‘The greatest part of a writer's time is spent in reading, in order to write; a man will turn over half a library to make one book.’ Whirld ransacked a world of libraries, turned over a mountain of books, and racked up six decades of reading, to make this one book.

Once upon a time, I loved a Jamaican beauty who loved film, fashion, and figure skating. A few glamour magazines passed under her eyes with some regularity, but books never really burdened her. She used to say, ‘Jerome, I don’t think we have anything in common. Except That!’ But she liked to hang out with me in my study, among the books. One night she came in, stood to the side, cocked her hip, and rolled her head in what seemed like awe, surveyed the dukedom of infinite riches, the mosaic of so many titles on so many shelves, and said, ‘Jerome, this room just makes you read!’ High praise and affirmation. Likewise, I sincerely hope that this Whirld just makes you read.

That reminds me of my favorite alphabet story. I often volunteered at a free legal clinic in San Francisco. There I met a man from Belize in the United States legally, enterprising and eager to learn. ‘Jerome,’ he would say, ‘I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, and I don’t do drugs.’ He was unaware of the stiff penalties that might bar re-entry to the U.S. if he overstayed his visa. He earnestly wanted to stay because he said he had the opportunity to learn things here that he could not learn in Belize. I advised that if he complied with the visa, he would improve his chances to return and stay legally.

Then, I saw him several months later. He had taken my advice and made a successful, legal, return. I had gained his confidence, and now he wanted to tell me something no one else knew. He told me he could not read. I said, ‘Well let me ask you this. Do you know your ABC’s?’ He brightened and said, ‘Yes’. I said, ‘I don’t think it’s fair to say you can’t read. You know your ABC’s. They are the foundation of reading. Let’s agree that you just need to improve your reading skills.’ We agreed.

I told him we could meet at the Main Library and I could show him what I meant about the ABC’s. He said the following morning would be great, so we met then. I demonstrated several ways in which the ABC’s made knowledge accessible there. Most memorable was our time with the elephant-folio atlases. We used them to locate a map showing San Francisco, and each of our birth places. We found them in the index as he sounded out and named the first letters of the locations. I also pointed out the free program at the Library to help with basic reading skills. In no time he was enrolled in that program, and another like it elsewhere. He excelled in his effort to improve those skills. He is now an avid reader and a citizen of the United States. He is an inspiration. Reading is transformative. Here, too, in this Whirld, the ABC’s have power and work wonders. Don’t they tell all the great stories?

The Nature of this Whirld

Camerado, this is no book, / Who touches this, touches a man

Whirld abounds in wit, character, scope, concision, pith and pluck and dash. It is particularly bookish, metaphysical, and ironic. Robust in history, poetry, and philosophy. It is a book about books, and an antidote to bibliomania (book madness). Its aim is above all to delight.

A Whirld of Words is the product of a reading life; I am a part of all that I have read. This is a dictionary for serious readers, compiled by a studiously serious reader. But, it never meant to be a dictionary! It started life in all humility as a discrete word list of instances where authors gave straightforward definition to words in some striking or insightful manner. It was a solitary undertaking. Like the English dictionary it reveres, this one was brought into existence – without any patronage of the great; not in the soft obscurities of retirement, or under the shelter of academick bowers, but amidst inconvenience and distraction.

The Greeks were accustomed to put a star or an X, which signified useful, as a sign on the margin of books in order to draw attention to striking passages.

Early in my reading career I learned to mark up my books rigorously, noting things of particular interest, elegance, or notoriety, making a special note of terms defined, and theses and conclusions stated by the author. In more recent years I realized I could not keep accumulating books endlessly, and when dictation and bibliographic software matured to the point of usefulness, I embarked on a campaign to collect the marked passages in my library and my adversaria (marginal notes) into computer files. Whirld started as a way of organizing a certain category of notes from reading. Call them commonplace definitions. It was an organic process. Naturally occuring. Finding definitions in their natural habitat.

I applied myself to the perusal of our writers; and noting whatever might be of use to ascertain or illustrate any word or phrase, accumulated in time the materials of a dictionary.

Like that eminence, Edward Gibbon, my own amusement was my motive and my reward. Mine would not be the fate of John Pytches who was driven mad by the gigantic dictionary he planned. I chose a benign method. I skipped the planning and moved directly into the compiling. I channeled the instincts of a bee. As you probably know, readers are sweet on bee metaphors.

To read means to borrow; to create out of one’s readings is paying off one’s debts.

This dictionary wrote itself, in advance. The world's greatest wordsmiths were employed; pressed into duty, really. Shanghaied. The definitions, descriptions, and portraits were waiting, like pollen at its highest pluck. My task only to light on the greatest flowers and suckle the juiciest flingwidge. Here is the honey, Honey. Gathered from the most industrious, percipient, and expressive bees from all times, all climes. For good reason, bees are also the universal metaphor of compilers throughout the ages.

‘I have laboriously collected this cento out of divers writers. I have wronged no authors but given every man his own. These do little harm and damage no one in extracting honey; I can say of myself, whom have I injured?’ Robert Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy

The art of literary mosaic was perfected by Robert Burton and he remains its unapproachable master. Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy was a book that Dr Johnson loved and admired above almost all others. Just as Burton said of his book, I can say of Whirld: omne meum, nihil meum, ‘tis all mine and none mine.

And, with Seneca, we say: quicquid bene dictum est ab ullo, meum est, whatever has been well said by anyone is my property. Gibbon listed the 'humble, though indispensable, virtues of a compiler' as 'method, choice, and fidelity'. We concur.

Whirld is a symposium of conversations. It occurs all around the world, and through the ages, with contributions from the very best minds; the community of mind.

The subject of quotation being introduced, Mr. Wilkes censured it as pedantry. Johnson. ‘No, Sir, it is a good thing; there is a community of mind in it. Classical quotation is the parole of literary men all over the world.’

Here, one is in august company, in the league of devoted readers, astute thinkers, and preeminent writers.

Aristotle insists on the value of what he calls 'reputable opinions'. In the Topics, a work primarily concerned with reasoning from and about 'reputable opinions', he advises us to collect such opinions and to use them as starting-points for our inquiries.

Dr Johnson’s scheme was to include all that was pleasing or useful in English literature.

I therefore extracted from philosophers principles of science; from historians remarkable facts; from divines striking exhortations; and from poets beautiful descriptions, [and made] this accumulation of elegance and wisdom into an alphabetical series.

We look at the world through lenses ground by our intellectual ancestry. Whirld’s authorities were selected for pertinence, eminence, and eloquence; as points of reference, like the stars in a galaxy. Whirld is a vicarious experience: You insert yourself into a conversation among an international aristocracy of thinkers and writers that threads through the ages, and includes you in. In that way, you enjoy what David Hume calls that liberty and facility of thought and expression which can only be acquired by conversation. Vicarious conversation included. Taste will also derive from absorbing these texts. Here you will, gain access to the propagators of knowledge, and understand the teachers of truth.

I hope you will find Whirld a sweet harvest from a busy reader. Culled, garnered, gathered, selected: the method – the systematic and thorough combing of great books for insight and definition. As Dr Johnson advised, words must be sought where they are used. There is no better summation of the methodology of Whirld than that. And, did they not gratify the mind, by affording a kind of intellectual history.

Dictionaries and Dictioneers

Diction – word choice: dictionary – words to choose from. A dictionary is an alphabetical list of words with meanings. An encyclopedia is a collection of essays about all knowledge arranged alphabetically. A glossary is a brief dictionary alphabetically listing terms or words relating to a specific subject or text, often with explanations. A commonplace book is:

an object emblematic of humanist reading, both a pedagogical instrument that every schoolchild or university student was expected to keep and an indispensable accompaniment to scholarly reading. The reader, apprentice or expert, copied into notebooks organized by topics or rubrics, fragments of texts that he had read that struck him for their grammatical interest, their factual content, or their usefulness as demonstrative examples.

Whirld has a place among and much in common with all of the above.

Aristotle recommends that 'one should make excerpts from written accounts, making lists separately for each subject’. Jerome, like A.E. Housman, appears to have kept a special notebook for quotations and allusions and other choice items. In the Renaissance:

the goal of reading was the construction of a storehouse, or library, a thesaurus (‘treasury’ or ‘storehouse’) of useful phrases, passages, and ideas. Annotations entered directly in the margins of books were a common and economical method. But Renaissance readers also used notebooks, often organized by a set of preconceived subjects or ‘topics’ (i.e., loci communes or common places).

Like a thesaurus, Whirld is a treasury; it is a veritable library, all fabricated, designed and furnished to be appealing and useful to you.

Commonplace books have a rich, long, and enduring history, and a significant bibliography. Whirld proudly joins this pageant. Much on the subject can be surveyed in Whirld.

What we call a commonplace book is anything but commonplace; they are unique records of personal interest and achievement. In the strictest sense, the term 'commonplace book' refers to a collection of well-known or personally meaningful textual excerpts organized under individual thematic headings.

A reader of dictionaries must be a rarity, or a captive, maybe an insanity. But I confess, I have read dictionaries, small encyclopedias, gaggles of glossaries, and word lists in several languages. Others have read a dictionary in prison. Most great dictionaries have readable elements, but a readable dictionary is a rare book indeed. Whirld is a dictionary meant to be read.

Johnson's prodigious reading was the foundation of his defining and his dictionary. It was his familiarity with this glorious language, his love of it, and his aptitude for its expression, that make so much of his great Dictionary readable still. Macaulay said, ‘It was indeed the first dictionary which could be read with pleasure’. After Dictionary Johnson, the competition is thin. Whirld aspires to this rarity, nobility, and distinction.

The sense that knowledge, although it may never be perfected, is best managed in small, compact pieces, which can be gradually assembled into wholes, is one of the deepest epistemological assumptions in Johnson’s Dictionary.

John Florio bewitched the Elizabethan elites with his Italian lessons, Renaissance vogue; enriched the language of his contemporaries, Shakespeare, et al., with his dictionary, A Worlde of Wordes; and tendered Montaigne to the English-speaking world. Johnson’s pertinent words and thoughts float through this Introduction, and beyond. The colossus speaks here for himself. It was scholar-

dictioneer – A highly evolved arbiter of diction, working largely solitary, and without safety nets, to define the world for the benefit of others, joining a brilliant constellation in the galaxy of lexicography

philologist Murray and his armament that made the New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (the NED) so readable and so remarkable; awesome. Of course, it was Oxford that commandeered it and made it the OED, and readily available. I also must confess an inordinate fondness for the cantankerous, heretical, inimitable Bierce, a fellow San Francisco dictioneer. ‘Do not trust humanity,’ Ambrose said, ‘without collateral security; it will play you some scurvy trick.’ These top dog dictioneers are my trade union.

My Websters

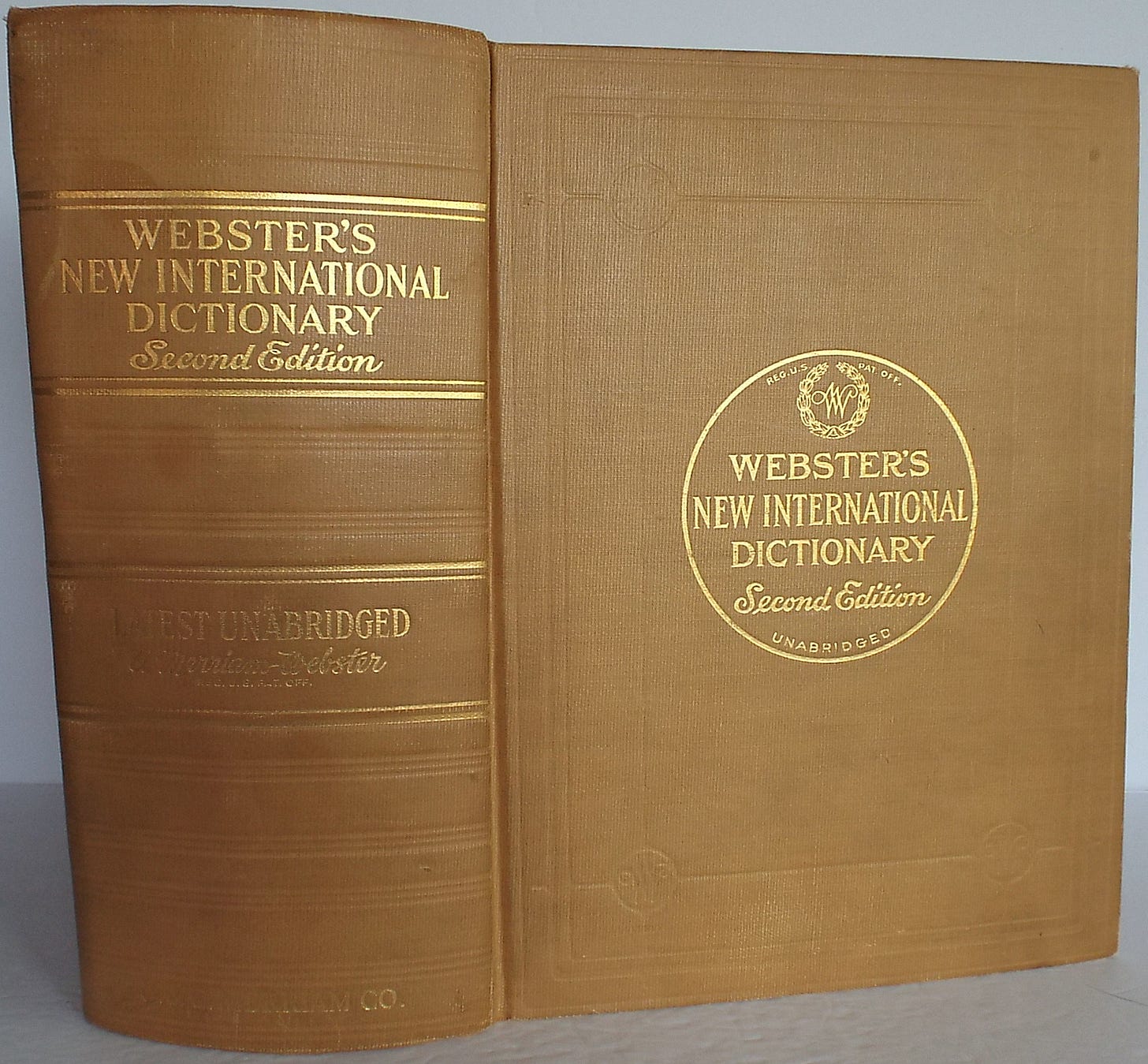

My Websters reflect the state of the language when I debuted on the planet. The state of the language was excellent. It was my good fortune to be born into a golden age of American dictionaries. I say that because of the two specimens that came to me in my early youth, and that I treasure to this day. The first was an inspired gift from my mother.

In 1953, Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language appeared. Edited by David B. Guralnik and Joseph H. Friend, it simplified its technical definitions to make them more understandable to the layman, gave full etymologies.

The design and format were salutary. Nothing seemed superfluous. The dictionary gave etymologies and data on the development of words that were especially finely wrought and apropos. It also featured exposition of the relationship of words to other languages, and labeled words which have a distinctly American origin. This Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language is exemplary in every way.

My father built a lot of homes for high school teachers when high school teachers could afford spacious new homes to raise families in. His goodwill brought me a library of books from a high school English teacher who accepted a promotion and position in a neighboring state. His dislocation delivered many boxes of books to me. It was a literary banquet. He was generous. Reading those many books he passed on was gratifying. But much more was included. There was a giant, golden nugget in my trove:

The second edition of Webster's New International Dictionary appeared in 1934 and takes the prize as the largest lexicon in English, with 600,000 vocabulary entries. Its pronunciations retained Webster's Eastern, conservative bias. Its coverage of both current and obsolete and rare terms was immense, and the second edition still figures in the minds of many middle-aged and elderly Americans as the dictionary par excellence.

Count me all in on that last point. My new Webster’s International was a monster tome, deaccessioned from the local high school library when the Third appeared, and still, now, a cornerstone of my learning. It was somewhat worn and had enjoyed already a noble, useful life. But it retained a voluptuous golden hue reflecting the Age. It is still at work, on the job, today. It is lavishly illustrated. As time passes its magnificence is only magnified. As it relates to the American language, it is a sacred object.

The Websters

In lexicography, as in other arts, naked science is too delicate for the purposes of life.

Ambrose Bierce gave definition to the truth hiding within the words we use to hide ourselves and our intentions. Likewise, Thomas Wyatt: well to say and so to mene, that swete acord is seldom sene. In guile, like Gonerils, we employ that glib and oily art, to speak and purpose not. Bierce, with his Devil’s Dictionary, arouses the sense of the irony, impertinence, and innuendo we find in so many words that is not adequately communicated by the likes of an International Dictionary. An International Dictionary is a political instrument. It has guard rails. It has been spayed, neutered and spindled.

Lexicographers are the weirdos in the room: they'll rhapsodize about the word itself, talk endlessly about the etymology or history of usage, give you weird facts about how Shakespeare or David Foster Wallace used the word. But ask them to comment on the thing that word represents, and they fidget. Ask them to do that with a word whose use and meaning describe systems, beliefs, and attitudes that have shaped Western culture, and they will do their damnedest to leave the room as quickly and quietly as possible.

A Whirld of Words is unconventional and contrarian. It breaks many of the cardinal rules customary to Websters dictionaries with the glee of hurled champagne flutes cracking on massive marble mantelpieces. It lacks much of their baggage as well. A Whirld of Words is liberal in its principles of inclusion, illustration, and robust expression of opinion. Websters dictionaries, in comparison, are tight-ass affairs. A Whirld of Words likes smart, opinionated, expression. It promotes and delivers pluck and dash in diction. What Websters withhold – what is said behind their backs about words and their meanings; that which Websters lexicographers pass over in tremulous silence – might be found here.

Taking a perspective from a self-described ‘epistemophilic dork’ reporting from the ‘Center of the Lexical Universe’:

As it turns out, there are several kinds of defining in the world, but the two big ones that lexicographers must wrestle with are real defining and lexical defining. Real defining is the stuff of philosophy and theology: it is the attempt to describe the essential nature of something. Real defining answers questions like 'What is truth?' 'What is love?' Lexicographers don't do real defining. In fact, the hallmark of bad lexicography is the attempt to do real defining. Lexicographers only get to do lexical defining, which is the attempt to describe how a word is used and what it is used to mean in a particular setting.

dicbot – a tight-ass, obsessive-compulsive drone programmed for conformity, pressing words into captivity, and producing industrial strength Websters. A term used only in jest.

Websters lexicographers must become dicbots, programmed for conformity – said in jest, because in truth, I love these people, with a deep and abiding love, just as I love and revere their work product. Just as I love librarians, and people who rescue others from drowning, flames, and trauma.

Like psychologists, or Sigmund Fraud (sic) himself, lexicographers often seem to have no sense of humor, or irony. They dare not. But the stereotype comes apart at the 'seems' when you read Word by Word by Kory Stamper. Don’t take my word for anything. Go read the book. Tolle lege. You will see. And there you will experience the quirky humor that percolates in the world of lexicographers. My Whirld is riddled with humor, too.

It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage, or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause, and diligence without reward. Among these unhappy mortals is the writer of dictionaries, the humble drudge. Every other authour may aspire to praise; the lexicographer can only hope to escape reproach.

Dictionaries are fraught with submerged ideas, narratives and histories. Here ideas, narratives and histories emerge, take the stage, and make a show, they unabashedly assert themselves. Websters wrestle words to the ground, to sedate them, pin them, and bind them like some Swiftian hulk, cocooned. Whirld gives them free range, observes them in habitat. Websters is a diorama; Whirld takes you to the savanna to run with the wild cats.

Whirld Perspective

Whirld is not agnostic; it finds logos ubiquitous in our universe. Atheists will find God here, believers will find atheists. Whirld does not subscribe to The Great Dichotomy, the separation of Spirit and Matter. Whirld is not intended as a balanced offering. Neither is it unbalanced. It is simply reflective of one person's life of mature reading, and of the authors he found most informative and enlightening in giving meaning to certain words, or some rich portrait or description. The balance is in the art and variety of the entries.

I, who do not form, but register the language; who do not teach men how they should think, but relate how they have hitherto expressed their thoughts.

Whirld reveals the bent of my reading and therefore of my mind, neither atheist nor aristocrat. I detest nihilism. I like the best of every good thing. Whirld has a definite bias toward truth. It is not indifferent, nor is it tepid. It is not trying to settle disputes; but will happily stir up a few in the minds of its readers. It relishes wit, and aspires to be a dictionary to inform judgment. Let it be the parole of literary people throughout the world.

Selection Criteria

This dictionary is about love – the love of words and ideas, the love of poetry and history, a love of all things biblio-related, manuscript and print traditions, libraries and languages, alphabets and annals. Whirld is filled with stimulating entries that can be read and reread with profit and pleasure. Some entries were selected where the mere existence of a word is remarkable, some to highlight the concept, context, or circumstance of a word, or, where the origins of the word are instructive, where a particular usage of a word brings richness, scope or intrigue; where a special meaning is revealed in an expression and in a way that delights the mind. Whirld will light up your synapses like the night sky on the 4th of July.

There is a liberal acceptance of novelty, variety, and contradiction in these entries. This is no place for cliché. Whirld can be disparate, refractive, suggestive, and reflective. It focusses on the operative word; many entries have multiple competitors. Some entries, especially the more robust, develop their own dialectic – a path of inquiry.

Just as the Warburg Institute in London arranged their books so that readers who looked for a particular book in the stacks would be surprised and edified by the others next to it, Whirld seeks to surprise and edify in the selection and arrangement of its entries.

When words penetrate deep into us they change the chemistry of the soul.

You will see how the entries often converse, or contend, with one another. By its nature, A Whirld of Words is evocative. The entries tend to be vivid and lively, and may poke and provoke. Some entries will act like a fish hook and yank you out of your element. Whirld will change your view of dozens of words, maybe whole subjects. It has been said that it is the great excellence of a writer to put into her book as much as her book will hold. We hope the same might be said of the compiler, and this book. Here, we include as much, and as many, as might be held between boards.

One acquaintance meant when she talked about Johnson's capacity to ‘tear out the heart of [a book]’ his power to see and extract its topics or key words.

Here are the primary criteria for selection and inclusion of entries in A Whirld of Words. The definition, use, mention, or illustration of a word, person, or event must make its mark for entry as follows:

Sublime the pleasure of perfection in expression

Perspicacious the insight of genius

Memorable something to return to because it keeps speaking

Provocative it awakens the spirit

Intriguing it stimulates the mind

Definitive in a superlative way

Arcane not familiar, but providing peculiar and welcome depth in understanding of what we love or revere

Words

As we learn from Wallace Stevens: It is a world of words to the end of it. Words are the soul of existence. In the end there is the word, and the word will abide. It seems divine, that within us and without us words connect us to purpose in existence, elevate and enlighten us even where life is mysterious or opaque, and purpose seems elusive and enigmatic. Just as words are signs for the things we encounter and experience, so is the created world, in our brains, our bodies, and the matter we perceive, an expression, a sign of signs, that the word will abide, and so will souls. Karl Kraus opines that: there is a pre-established harmony of word and world, and that the cosmos of one is reflected in the other. While pyramids crumble, papyrus preserves the words. After empires expire, their words still have breath, life. Words survive. Expression drives human destiny, the destiny and distinction of the species. Words are the alpha and omega of existence.

Words too have souls, character, and personalities – all words – not just our common onomatopoetic friends who can hiss, splutter, lisp and flummox. Words came before thought. The first words uttered were, naturally, poetic – onomatopoetic expressions of profound emotion. Diaphragmatic. Thymotic – expressions from the gut brain, our enteric self.

Words have a life. Words want to work, they want to please. They will fetch. They will hunt. They like to run and play. They sing and dance. Words take great pride in a job well done. They are team players. They are ecumenical, mostly tolerant, though there are some deep conflicts and antagonisms. So many words are slanted, skewed or biased. Words have character, hue, timbre. Every word ever uttered is a subtlety.

Defining

The great labour – interpreting words and phrases with brevity, fulness and perspicuity.

Aristotle says a definition is a phrase signifying a thing's essence and that definitions require only to be understood. Augustine says the science of definition, division, and partition is not instituted by men; rather it was discovered in the order of things. Nietzsche says nothing is definable unless it has no history. Newman says we conceive by means of definition or description. Ortega y Gasset says to define is to exclude and deny.

The art of definition is the art of balance, of abbreviating without impoverishing.

This dictionary is not intended to be definitive or conclusive. In some ways, Whirld begins where definitions leave off, fail, or are indefinite. Strictly speaking, definitions set limits that words don’t always observe. Words migrate, oscillate, gravitate, and bloviate. Words can be chameleons.

We define only out of despair.

Meaning

The criterion of logos, coherent speech, is not truth or falsehood but meaning. Words as such are neither true nor false.

A definition is just the beginning of getting to the meaning of a word.

It is not sufficient that a word is found, unless it be so combined as that its meaning is apparently determined by the tract and tenour of the sentence; such passages I have therefore chosen, and when it happened that any authour gave a definition of a term, or such an explanation as is equivalent to a definition, I have placed his authority.

The meaning of words exceeds their definition. Definition is a lurch into certainty, idealization.

To know what a specific word means one has to know the words which, so to speak, hedge it in.

Words that work fit in. They connect. They support and elucidate their neighbors. In turn, they are defined by context and the integrity of the expression where they appear:

some shining with sparks of imagination, and some replete with treasures of wisdom.

Language

My high school Latin teacher had a barrel chest that could not be contained by any sport coat. His wiry hair ascended and extended it seemed to infinity, like Wittgenstein’s. He had a thick cardboard tube from wrapping paper that he would slap on his desk to get our attention. It popped and resounded like a megaphone and was quite effective. He called it his ‘pummeling stick’. I never saw or heard of him using it on a human being; the mere sound of the threat of pummeling apparently was sufficient to establish and maintain order. On one memorable occasion, the stick got three quick cracks. ‘Gentlemen(!)’, he bellowed in colossal frustration, ‘Gentlemen(!) Tonight, sleep with your Latin books under your pillows. Maybe you will get it by osmosis(!)’ Inventive. May Whirld be osmotic, too. More of a doorstop than a pillow; I won’t recommend sleeping with it, though you are welcome. But do keep it nearby; handy, patient, and friendly. It will absorb you, if you allow it. A silent companion, waiting to speak with you, a friend to your solitude.

Well, Latin and a little Greek have made a way osmotically into my Whirld. Latin, while dead, can still be flogged. It is now vestigial, emblematic, iconic, and inherent in English. But still daunting to most of us. Most of the Latin here is Englished. Trust me, you should have no problem following along. You already have done quite well. Carry on. If you do face a problem, use the internet, or just forget about it. This is not a test. And have fun with the little Greek you find here. Just remember, the ancient Greeks did not mis-spend their youth learning dead languages! And they were no intellectual slackers.

Imagine the worst epitaph: ‘Can you believe this? A man who NEVER! turned a phrase!’ Vince had heard me come into the dorm room, and turning, he looked up from the book he had just finished reading, Madame Bovary. He was of course referring to Charles Bovary. Visible chagrin. Incredulity. His mouth gaped, aghast, as one saw the pallor of mortification materialize, the horror comprehended.

Vince's word IQ was more than two and a half standard deviations strong – i.e., off the charts. I added ‘bruit’ and ‘puling’ to my vocabulary in my first conversation with him when he quoted from the exam they gave him to pass out of the freshman 'Rhetoric' requirement. At the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, near the Pyramid of Cestius (where also lies the infamous Shelley, destined for a lower location), I saw him weep at the grave of the celestial Keats. ‘He wrote the greatest poetry in the English language before he was twenty-five!’, the nineteen-year-old college poet wailed through tears in anxious anguish. It was, of course, John Keats who said, ‘I look upon a fine phrase like a lover!’ My Whirld is brimming with phrases to love; enough to make a poet weep.

Language has the peculiar distinction of being antiquarian and avant-garde at the same time; English more than any other. Add to that the proclivity of English to pilfer freely for what it lacks or needs, or just likes, from all other languages, and you have the veritable juggernaut of world languages. It vacuums up words with abandon, and cares not whether the plundered language is living or dead. Like a thug, it runs amok.

A Better Whirld

Dear Reader, you can do better. This dictionary is stipulated to be incomplete and to invite additional effort and input by the consumer.

In this work, when it shall be found that much is omitted, let it not be forgotten that much likewise is performed.

You will find countless omissions – words, apt quotations, authors, books, cultures, disciplines, languages. But, the deficiencies of this work are merely a challenge. You could do better – much better.

But please don’t dwell on the faults in my Whirld. Rather, focus on how this work would be improved and superseded with your own contributions, interests, studies, and perspectives. I leave that to your imagination. The best Whirld will be the one you make.

Farewell Whirld

Words are the only things that last for ever.

Old dictioneers never die, they just get redefined. The tomb of Thomas Lucy depicts shelves of his favorite books. Let this tome, this library, this Whirld, be my tomb. Here my spirit will rest, abiding with the word and the wordsmiths. Booked for life in death.

To live on, when I am gone to the shadows. (Fort zu leben, wenn ich abgeschieden.)

And so Dear Redre, only the words will remain. 550,000 of them, from abba to Zeus, competing here for your attention. They are my happy bequest to you.

Please take delight, and enjoy!

Bees work for man; and yet they never bruise

Their master's flower, but leave it, having done,

As fair as ever, and as fit to use;

So both the flower doth stay, and honey run.

A Worlde of Wordes is FREE.

Notes

Quotations from the Preface of Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) appear in bold, italic typeface throughout the Introduction.

O Redre: And patientely, O Redre, I the praye, / Take in good parte this worke as yt ys mente (Wyatt 1963) p. 132

the purpose of this book; (Miller 1969) p. 11

New English Dictionary; A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, 1884-1920. Reissued as The Oxford English Dictionary, 1933

read everything; Jerome, paraphrasing 1 Thess. 5.21, (Williams 2006) p. 256

a well-known dictum of Hugh of St. Victor; (Duggan et al. 2004) p. 293

the best provision; (Montaigne 1958) p. 628

a writer's time; (Boswell 1952) p. 523

Camerado, this is no book; Walt Whitman, (Fischer 2003) p. 288

the Greeks were accustomed; (Thompson 1962) p. 50

my own amusement is my motive; (Craddock 1989) p. 89

John Pytches; (P. Johnson 1991) p. 750

to read means to borrow; (Lichtenberg 1959) p. 62

I have laboriously collected this cento; (Bettmann 1987) frontis

the art of literary mosaic; (Jackson 1981) p. 18

a book that Dr Johnson loved; (DeMaria 1986) p. 31

tis all mine and none mine; (Jackson 1981) p. 23

whatever has been well said; Seneca, Epistolae, xvi, 7 (Jackson 1981) p. 23

humble, though indispensable, virtues of a compiler; (Gibbon 2005) p. cviii

the subject of quotation; (Boswell 1952) p. 974

Aristotle insists; (Hare et al. 1991) p. 105

we look at the world through lenses; (Heschel 1951) p. 235

what David Hume calls; (Hume 1965) p. 39

an object emblematic of humanist reading; (Cavallo et al. 1999) p. 29

one should make excerpts; (Hare et al. 1991) p. 103

a special notebook; (Cameron 2011) p. 406, 772

the goal of reading; (Sherman 1995) p. 33, 60

what we call a commonplace book; (Havens 2001) p. 7

Malcolm X read a dictionary in prison; (DeMaria 1986) p. ix

the first dictionary which could be read with pleasure; (Macaulay 1888) p. 296

the sense that knowledge; (DeMaria 1986) p. 39

do not trust humanity; (Fatout 1951) p. 94

Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language; (Landau 1984) p. 73

Webster's New International Dictionary; (Landau 1984) p. 64

in lexicography; (S. Johnson 2002) p. 566

well to say and so to mene; (Tottel et al. 1965) p. 80

that glib and oily art; (Shakespeare 2000) p. 111

lexicographers are the weirdos in the room; (Stamper 2017) p. 232

there are several kinds of defining; (Stamper 2017) p. 94, 95

the stereotype comes apart; Word by Word by Kory Stamper, (Stamper 2017)

dictionaries are fraught; (Hitchings 2005) p. 110

the Warburg Institute; (Grafton 2009) p. 291

when words penetrate deep into us; (Levertov 1973) p. 114

Johnson's capacity to tear out the heart of [a book]; (Boswell 3: 285), (DeMaria 1986) p. 35

it is a world of words; (Stevens 1982) p. 345

there is a pre-established harmony; as Frederick Ungar put it (Kraus 1974) p. xvii

the great labour; (S. Johnson 2002) p. 573

Aristotle; (Aristotle 1990) p. 144

Augustine; (Augustine 1964) p. 70

Nietzsche; (Hayman 1980) p. 1

Newman; (Newman 1960) p. 77

Ortega y Gasset; (Ortega y Gasset 1961) p. 99

the art of definition is the art of balance; (Hitchings 2005) p. 86

we define only out of despair; (Cioran 1998) p. 48

the criterion of logos; (Arendt 1978) p. 98

to know what a specific word means; (Miller 1969) p. 49

I look upon a fine phrase; (Keats 2001) p. 487

words are the only things that last for ever; (Hazlitt 1908) p. 107

the tomb of Thomas Lucy; (Palmer and Palmer 1981) p. 156

to live on when I am gone to the shadows; (Kraus 1977) p. 13

bees work for man; (Herbert 2015) p. 113

Works Cited in the Introduction

Arendt, Hannah (1978), Thinking (The Life of the Mind, Vol.1; New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich) xii, 258.

Aristotle (1990), Prior Analytics; Posterior Analytics; Topics; Sophistical Refutations; Heavens; Metaphysics; Soul; Memory Vol. I (Great Books of the Western World, 7: Encyclopaedia Britannica) viii, 726.

Augustine (1964), The Essential Augustine (New York: New American Library) 272.

Bettmann, Otto (1987), The Delights of Reading: Quotes, Notes and Anecdotes (Boston: Godine) xiii, 139.

Boswell, James (1952), The Life of Samuel Johnson (New York: Modern Library) xv, 1 , 559.

Cameron, Alan (2011), The Last Pagans of Rome (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press) x, 878.

Cavallo, Guglielmo, Chartier, Roger, and Cochrane, Lydia G. (1999), A History of Reading in the West (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) viii, 478.

Cioran, E. M. (1998), A Short History of Decay (New York: Arcade) 181.

Craddock, Patricia B. (1989), Edward Gibbon, Luminous Historian, 1772-1794 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press) xv, 432.

DeMaria, Robert (1986), Johnson's Dictionary and the Language of Learning (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press) xii, 303.

Duggan, Anne, et al. (2004), Omnia Disce: Medieval Studies in Memory of Leonard Boyle, O.P (Burlington, VT: Ashgate) xvi, 322.

Fatout, Paul (1951), Ambrose Bierce: The Devil's Lexicographer (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press) xvi, 349.

Fischer, Steven R. (2003), A History of Reading (London: Reaktion) 384.

Gibbon, Edward (2005), The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire [Vol. 1] (London: Penguin) cxiii, 1114.

Grafton, Anthony (2009), Worlds Made by Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press) x, 422.

Hare, R. M., Barnes, Jonathan, and Chadwick, Henry (1991), Founders of Thought (New York: Oxford University Press) vi, 305.

Havens, Earle (2001), Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century (n.p.: Yale University) 99.

Hayman, Ronald (1980), Nietzsche: A Critical Life (New York: Oxford University Press) xxiii, 424, 4 l. of pl.

Hazlitt, William (1908), Table Talk; or, Original Essays (New York: E.P. Dutton) ix, 337.

Herbert, George (2015), The Complete Poetry (Penguin) lvii, 578.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua (1951), Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion (New York: Farrar, Straus & Young) 305.

Hitchings, Henry (2005), Defining the World: The Extraordinary Story of Dr. Johnson's Dictionary (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux) viii, 292.

Hume, David (1965), Of the Standard of Taste, and Other Essays (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill) xxviii, 183.

Jackson, Holbrook (1981), The Anatomy of Bibliomania (New York: Avenel Books) 668.

Johnson, Paul (1991), The Birth of the Modern: World Society, 1815-1830 (New York: HarperCollins) xx, 1095.

Johnson, Samuel (2002), Samuel Johnson's Dictionary: Selections from the 1755 Work that Defined the English Language (Delray Beach: Levenger Press) vii, 646.

Keats, John (2001), John Keats: The Major Works (New York: Oxford University Press) xxxvi, 667.

Kraus, Karl (1974), The Last Days of Mankind: A Tragedy in Five Acts, trans. Frederick Ungar (New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co.) xxii, 263.

--- (1977), No Compromise: Selected Writings of Karl Kraus (New York: Ungar) ix, 260.

Landau, Sidney I. (1984), Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography (New York: Scribner) xiii, 370.

Levertov, Denise (1973), The Poet in the World (New York: New Directions) x, 275.

Lichtenberg, Georg Christoph (1959), The Lichtenberg Reader: Selected Writings (Boston: Beacon Press) x, 196.

Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1888), Critical, Historical, and Miscellaneous Essays and Poems, 3 vols. (New York: H.M. Caldwell).

Miller, Henry (1969), The Books in My Life (New York: New Directions) 316.

Montaigne, Michel de (1958), Complete Essays (Stanford University Press) xxiii, 883.

Newman, John Henry (1960), An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (Garden City, NY: Doubleday) 434.

Ortega y Gasset, José (1961), The Modern Theme (New York: Harper) 152.

Palmer, Alan Warwick and Palmer, Veronica (1981), Who's Who in Shakespeare's England (New York: St. Martin's Press) xxvi, 280.

Shakespeare, William (2000), The History of King Lear (New York: Oxford University Press) x, 321.

Sherman, William H. (1995), John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) xiv, 291.

Stamper, Kory (2017), Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries (New York: Pantheon Books) xiv, 299.

Stevens, Wallace (1982), The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Vintage Books) xv, 534.

Thompson, James Westfall (1962), Ancient Libraries (London: Archon Books) 4 l., 120.

Tottel, Richard, et al. (1965), Tottel's Miscellany (1557-1587): Vol. 1, 2 vols. (Rev. edn.; Cambridge: Harvard University Press) xxi, 345.

Williams, Megan Hale (2006), The Monk and the Book: Jerome and the Making of Christian Scholarship (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) x, 315.

Wyatt, Thomas (1963), Collected Poems of Sir Thomas Wyatt (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) xlviii, 298.

I have been keeping commonplace books for over twenty years and now have ninety odd completed ones. As a side project I keep,a dictionary of unusual words I come across. The rest of my time I just waste!

Thank you for sharing this magnificent, and beneficent, portal into your mind. Really, there is a lot I want to talk about with you. I will make a special effort to read and reread this.

I'm working on a Commonplace Book right now. It's about many things on the topic of the Philosophy of Nature, but also Magic, and Food. It's called THIS IS GASTROMANCY.

You might like the Glossary. It is a work in progress:

https://thisisgastromancy.substack.com/p/glossary

And you might like my note about Character Writing:

https://substack.com/@kenscommonplacebook/note/c-97434420

I think well of you. I'll be seeing you.