Z E I T G E I S T

The Marginal Utility of Billionaires

RICH SAMMLER OBITUARY - GOLDEN GAZETTE

M I S I N G

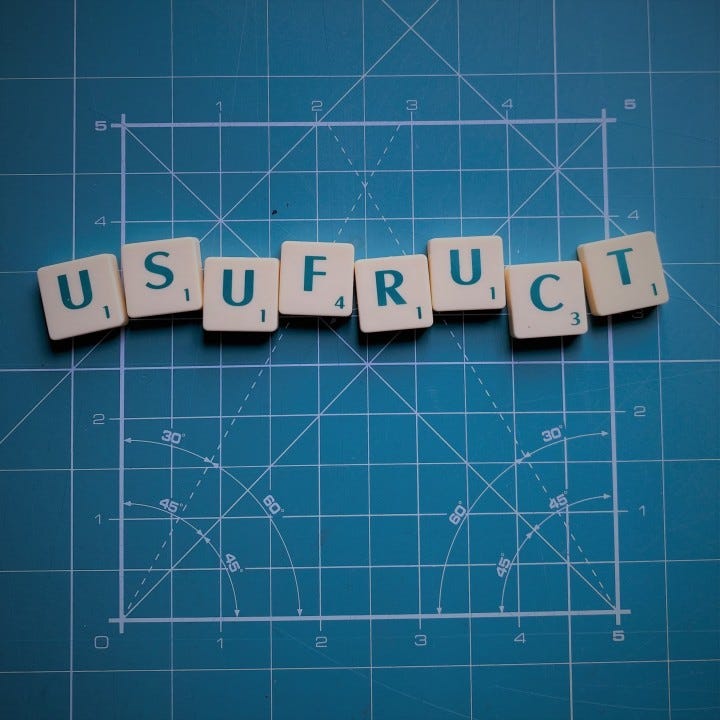

Ricardo Sammler, founder of PeerLink, Benefaction and Usufruct, developer of the Mutuality Model, dies at 37.

‘Extinguished by spontaneous evaporation,’ Ricardo ‘Rich’ Sammler, provocative author, serial entrepreneur, and astute social thinker, is thus deceased. The execution occurred at a secret military installation (believed to be an artificial atoll in the South Wuhan Sea) on orders of the Wuhan Global Security Commission, as of 12:05 a.m., 14 December 2029, according to an official notice.

Sammler was criminally charged by Wuhan, seized, and executed for ‘contumacious megalomania.’ The notice quotes Sammler at his death making the ambiguous assertion, ‘mistakes were made.’

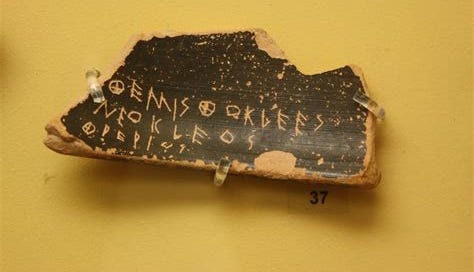

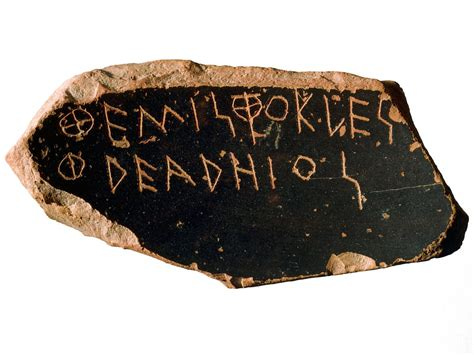

Wuhan authorities believe Sammler was the intelligence behind the recent stochastic assassinations of twenty-seven ranking members of the former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) precipitated by the Ostraka Manifesto. Ostraka is the clandestine ‘arbiter of equity’ issuing the annual global survey of offensive fortunes identified for decimation. Those persons holding excessive fortunes according to Ostraka’s indictments are ‘licensed’ for elimination if they fail to promptly divest (‘disgorge’) sufficient wealth to fund poor persons and public benefits. Ostraka’s official communication insists that the assassins are autonomous, unaffiliated agents.

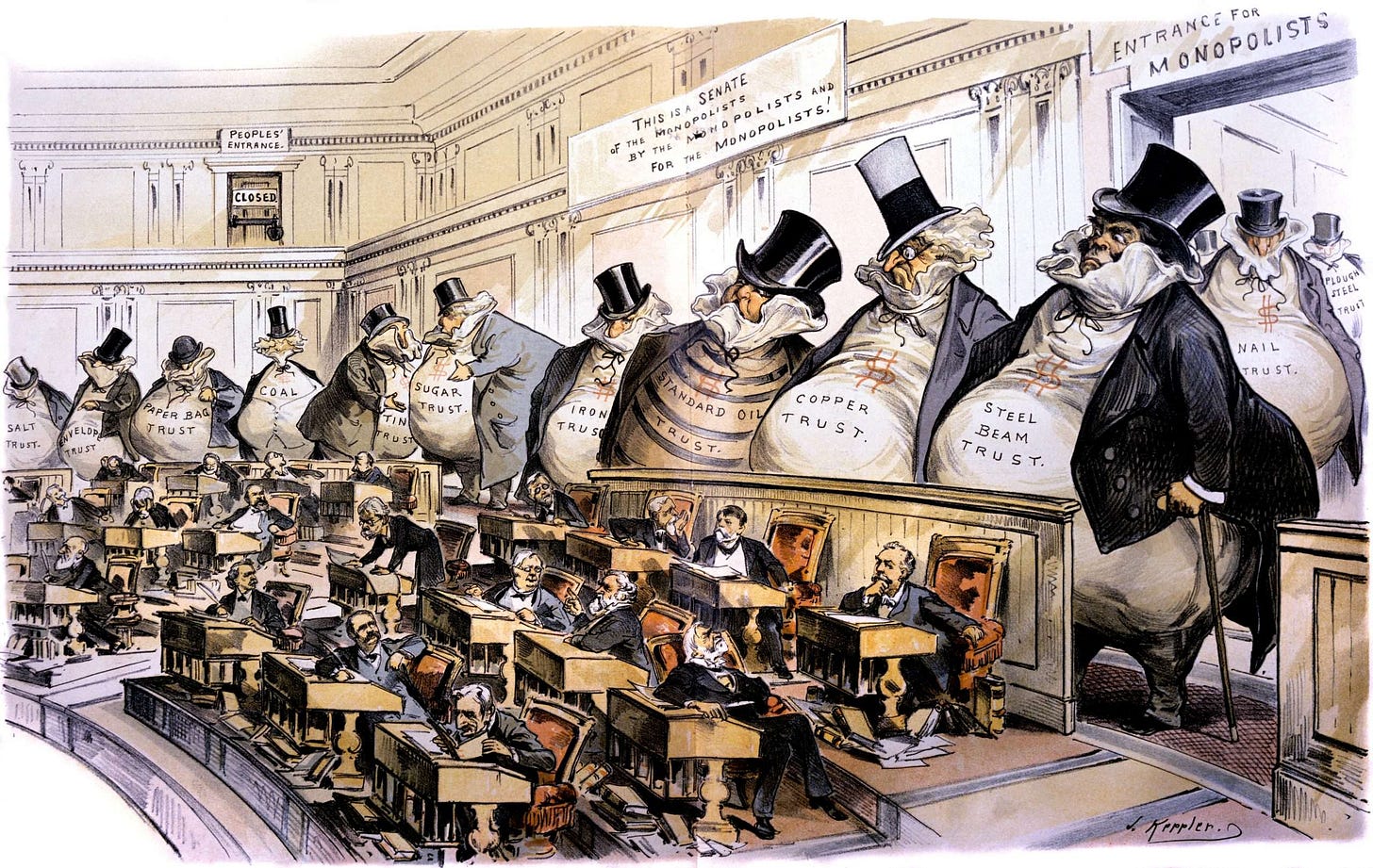

The first published findings of the Mutuality Model developed at Usufruct, Sammler’s social pioneering venture, robustly confirmed that while all societies favor the wealthy and are illiberal to some material degree on that account, the most rigged societies are the most illiberal societies. The Mutuality Model findings exposed the ‘endemic, widespread, staggering fraud, and systemic, deep rigging’ favoring CCP party elites and their plutocrat comrades. Civil unrest erupted almost instantaneously. A web of bubbles inflated by mammoth real estate frauds enriching the elites, burst in chorus. This precipitated the Wuhan World Recession.

In these most precarious social circumstances, Ostraka issued its first indictment, and the anonymous, solitary assassinations followed forthwith. The assassins were not waiting for the due process Ostraka avowed, and the social conflagration now commonly referred to as the ‘Plutocrat Panic’ broke out with the Ostraka ultimatum. The Panic, as has been widely reported, appears to have thwarted a planned imminent invasion of Taiwan, and inaugurated collapse of the CCP and prompt regime change to the reactionary Wuhan Global Security Commission after the failure. Wuhan immediately offered a massive bounty for the delivery of Sammler to their authority.

After going into hiding on California’s Lost Coast, Sammler was lured to a rendezvous and seized in San Francisco by subterfuge and transported across the international date line by ‘raptors,’ and delivered into the custody of Wuhan Global Security authorities. Sammler’s estranged wife has publicly asserted that she also was duped, and unwittingly facilitated Sammler’s seizure, insisting she had no complicity in the scheme.

Sammler, born in a hospital on the bluffs of the west bank of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota, remained deeply and demonstrably influenced by this origin. In his recently published ‘autobiographical romp,’ Mistake of Fact: An Unconventional Career in Law, he asserted that in his first published book, How the West Was Parched, he exercised a ‘unique qualification’ to analyze, explicate, and historicize the contrasting riparian (river front) rights to the use of water flowing in waterways on either side of the Mississippi. The book contrasted rights derived from common law, prorated by frontage, in the East, with those derived from Napoleonic Code law rights in the West, where priority descends from the source, and the one closest to the source may take all the water. Sammler found Code rights tyrannical and common law rights communitarian and equitable. Parched prompted a series of the most complex conflicts and legal disputes, legislation, and compacts between states.

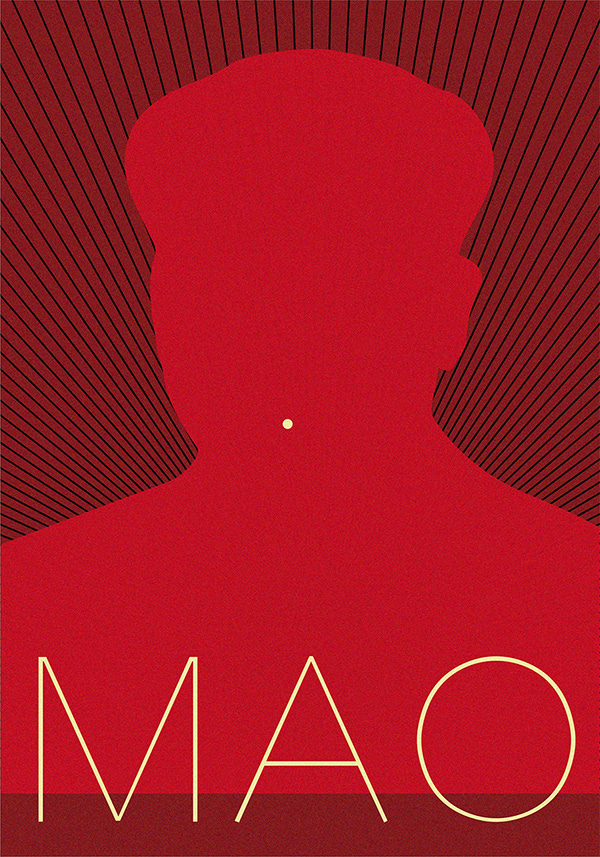

Considered a companion or coda to Parched, in an elaborate, critical article in Analemma entitled, ‘Maophistopheles: Materializing Hegemony’, Sammler dramatized the fierce contest and supremely consequential outcomes in the global contest to monopolize the extraction of essential mineral elements called ‘rare earths’, and advocated for a constitutional amendment and U.N. charter resolution asserting sovereign, inalienable rights of the People (‘livingbreathing’ human beings) to all fresh water, and to all nonrenewable subsoil natural resources on earth. The article improbably led to a collaboration on a movie script which garnered a nomination for an Academy Award. The film, Maophistopheles, was a major success in distribution, but was banned by the CCP and in the Wuhan Empire.

Sammler wrote extensively against the judicial fiction making persons of corporations, and in favor of a three strikes law for incapacitating corporate felons; about abridging the right to counsel and confidentiality for corporations, and making due process for entities subservient to the interests and rights of natural persons; and, about establishing a public safety duty to promptly disclose entity wrongdoing. He also advocated for radical simplifications of criminal law, and for the elimination of the federal individual income tax.

Sammler, with his wife, algorithmic genius Michelle ‘Riley’ Buridan, co-founded PeerLink, a California corporation that developed a peer-to-peer network operating system for personal computers. Sammler published his Magic Pen Series (offering popular Career Power Kits and Quantum Learning Capsules) while serving as chairman and chief executive of PeerLink. Sammler and Buridan formed the publishing venture, Iridium (‘self-improvement never stops’), to exploit the success of the Series.

The pair turned to the study and analysis of incentives as Sammler and Buridan partnered again to found Benefaction, a powerful reverse purchasing agent, distinguished by its systematic focus on incentive transactions, equitable pricing, and ‘beneficence discernment.’ Benefaction brokers success fees, rewards, and other incentives to match a customer specification with a provider of specific goods or services. The app agent expeditiously matches a specified need for a design, a plan, a fix, an innovation or solution, some code or an algorithm, an object, or a creative desire, with bids from qualified providers. This app fueled prodigious productivity and creativity according to rigorous customer surveys and fueled a fortune for the enterprising couple. Scammers, frauds, and pernicious or harmful offers were effectively disqualified from posting.

The ‘beneficence discernment factor’ was devised from a rigorous study and analysis using data from the autobiographies, profiles, and studies of the ‘sublime brains’ donated by the magnanimous School Sisters of Notre Dame from Mankato, Minnesota. Sammler credited Riley Buridan with “consummate intellectual virtuosity” for the penetrating breakthrough work leading to the development of this critical innovation. Sammler claimed it was the ‘good will factoring’ that gave Benefaction its commercial esteem and market dominance.

Cofounder Riley Buridan took command of Benefaction after a spectacular public offering that, as Buridan put it, “would make Croesus blush.” With the hyperwealth generated from the public offering of Benefaction, Sammler created Usufruct, his ‘social pioneering’ venture, and wrote ‘The Essay’: ‘On the Principle of Usufructation, Thoughts on the Marginal Utility of Plutocrats.’ The Essay first made him famous, then made him infamous.

The analysis for equitable pricing of bounties and rewards, key to the success and stellar reputation of Benefaction, yielded the fundamentals and clues that led to development, by Usufruct, of the Mutuality Model, an open source device to apply “equitable scrutiny” to wealth, and the analysis of the utility of inherited, dynastic, and generational wealth.

The Mutuality Model revealed deep and pervasive structures of systemic rigging of all factors of every economy in favor of the few, and an intricate web of corrupting associations that resemble far less sophisticated racketeering operations. The Mutuality Model has the power and perspicacity to discern the financial profile of any person or entity, to a level of detail that it could prepare all US tax returns or complete financial statements with its data and analysis. Though the conclusions were not entirely surprising to economists, the key, it was contended, was considering billionaire status as a factor in a market, subject to market forces, then found to be manifesting in vast negative opportunity costs. The Mutuality Model identifies wealth disequilibrations and beneficent remediations. The Model found a glut, ‘a most pernicious glut’ of obsessively self-aggrandizing great and generational fortunes.

Sammler said Usufruct was betrayed, alleging that it was his erstwhile friend and financial wizard, Luc de Soubrie, who orchestrated the Benefaction IPO, and who hijacked the Mutuality Model code before release, and may be the mind behind Ostraka. Riley Buridan married de Soubrie after her divorce from Sammler.

Some great businessmen do one big thing, some do a few, only a few do many great things. But business success was inadvertent for Sammler. And he called his career at law unconventional. He said he principally lived the life of the mind. He was a radical thinker; his thought penetrated to the roots of things. He was a seminal thinker; he fostered deep thought in others, and was emulated.

Riley Buridan would have Ricardo Sammler remembered this way: ‘Determined advocate, discriminating intellect,’ she said. ‘Friend of the good.’

Ricardo Sammler, an orphan, died without issue. Sammler’s entire estate was bequeathed to the Decima Beneficent Pledge Fund.

SAMMLER INTERVIEW WITH GOLDEN GAZETTE EDITORS

[This interview took place after the Wuhan Global Security Commission officially offered a $50B bounty for the delivery of Ricardo Sammler to their authority. The Editors met with Sammler at a secret location only days before his extinction was reported by the WGSC.]

GG: A prodigious bounty has been offered for your ultimate elimination by the Wuhan Global Security Commission. What do you know about this; what can you tell us?

RS: The Wuhan bounty will go to a lucky, perverse profiteer, if Wuhan has its way. I am not flattered by the threat of elimination. And yes, of course, the irony of offering a maleficent bounty for the life of the founder of beneficent Benefaction, and all the rest, is not lost on me. Some time ago, prior to the Wuhan threat, I decided to retire my public persona and slip back into my natural, preferred state of diffidence. What is more diffident than death? Not to be glib, but my lifelong dedication to social beneficence has been, in that solemn premise of philosophy, a preparation for death. Not saying I want to die, only that I am prepared to die.

GG: What did Riley Buridan, your former wife and business partner, mean when she testified before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that you inspired Ostraka? What was the nature of your involvement?

RS: Let me be honest. Killing billionaires was a surprise to me. Resentment is the flip side of admiration. Greed and insolence have unleashed a maelstrom of vengeance in the form of Ostraka. I have not plumbed the niceties of the economic logic of elimination. But I have to admit that there seemed to be an obvious historical necessity being executed in this exercise, even though to excess. I see this in retrospect. I certainly did not see it coming.

Plutocrats only respond to disincentives; the social ills they are responsible for cause resentment, rancor, and melancholy when exposed. Plutocrats are the most powerful people in society, and, as Samuel Johnson reminds us, ‘power and resentment are seldom strangers.’ The insolence of wealth and power naturally breed great resentments. The killers are terrorists; terrorism is an expression of frustration and resentment, forcing recognition of the blind hatred engendered by a perceived, grievous oppression. Capital punishment always seems excessive to me, even when it is earned and deserved. I recommended decimation of great fortunes as a deterrent and vent; death is also a deterrent that might encourage others to consider the alternative, but I will always advocate due process and the extinction of the death penalty.

Riley was simply referring to the Mutuality Model effectively being hijacked and corrupted into the awful designs of the Ostraka strike force. Riley was only implying that my work product was useful and influential, not that I had any direct or conspiratorial involvement. Note that in that testimony, when she was pressed on her husband’s role in the formation of Ostraka, she invoked a spousal privilege not to comment.

GG: You are referring to your erstwhile business associate Luc de Soubrie. Luc, you once said, led you to riches. His financial acumen is renowned. He married your ex-wife and, you have publicly and vociferously complained, he removed key ‘beneficence controls’ at Benefaction after you left. You called him “lucre Luc.” What caused the rift between you?

RS: Luc’s status envy. Luc insisted on being considered a ‘founder’ of PeerLink when it launched publicly, in the wayback time. Riley and I were the founders and we did not make this concession to Luc’s ego. Apparently he was mortally offended. He blamed me for the bruising, and never forgave. Thus was planted the seed of the resentment that proliferated into his malignant campaign to have ruin rain upon me, however long it might take and by whatever means. Luc is ruthless, venomous and sadistic; he means to dominate, even if he must destroy. Luc finally lost me with his lying.

I met Luc de Soubrie on a spacious balcony at a party on a hillside perch in Sausalito. His parents were French academics; Luc was an accountant, working in New York, aspiring to be a tech leader. Shortly after we met, Luc invited me to join him in Manhattan for a champagne party aboard a visiting French aircraft carrier. The craft was on a round-the-world cruise with the most recently graduated French naval cadets. Luc had done his military duty to France as an officer, and thus was welcome to the champagne, and could bring guests. By the time I left New York, I had recruited Luc to join PeerLink to steer our finances on a path to public offering, merger, or acquisition. He told me as a child he loved a comic strip called “Lucky Luc,” or, as he frenchified it, ‘Lukey Luc.’ He sold me on the “Lucky.” I must admit, I was duped by Luc. I have never been a malicious person but, I loathe Luc. I believe all our lives have purpose, and that presupposes a reckoning. Luc will have some serious explaining to do. Lukey Luc, now apparently hunkered in Hong Kong, abjectly idolizes wealth and power. Luc is the contumacious megalomaniac.

GG: You are now ultrawealthy and admired. You have given $450 billion dollars to your Decima Pledge Fund to distribute basic incomes beginning in the poorest nations. That is noble, but aren’t you, too, a plutocrat now?

RS: Ultrawealthy! Free from the burdens of life, not afflicted like others, making money while I sleep, sleek and sophisticated, living without impediments or obstructions. Cloaked in my pride, and blinded by arrogance, I can be presumptuous, imperious, ravenous, insatiable, and idolatrous with impunity. I don’t even see my inferiors; I ignore the judgment of others and sneer at opposition. I can sow discord, devour people as if they were bread, and crush the hopes of the poor, trapping them in sinister schemes. I am a corrupting influence and I don’t care!

That was the facetious-ultrawealthy me speaking. The actual factual metaphysical me says: sharing is majestic, hoarding is heinous. Justice and equity are twins. Beneficence is the highest good. My Mutuality Model promotes admiration for sharing, shame for hoarding wealth.

The good in each of us wants good to prevail; we yearn for the moral satisfaction in seeing good triumph. We deem ‘best’, those who prevail in the fortunes of life, even though luck is likely the dominant determining factor giving them prevalence. We assign all the ‘best’ attributes to them, because they seem to have everything else. We envy the wealthy and their presumed happiness. They must be happy, happier, happiest, mustn’t they? We prefer to see our own unfettered ambitions for success and happiness as possible; we see objectified in those whom fortune has most favored the satisfaction of our own craving for success and happiness. We admire success. Success is associated with wealth by default; we let the wealthy represent every success to confirm our biases. We all feel worthy of wealth, so we all identify with wealth in an imaginary way. We project our own fulfillment of desire onto the wealthy, like what Marx called a fetish, making objective what is really irrational, just a projection of desire and fulfillment.

Admiration of wealth is a strong bias of our species. Trial lawyers will tell you, people do not give up their biases. But, they might be persuaded to substitute a greater for a lesser bias in making a judgment. A stronger countervailing bias must be invoked to dislodge an adverse bias. When the Mutuality Model demonstratively revealed that cheating, fraud, grift, coercion and force in fact undergird all great fortunes, the reaction trumped the admiration bias. Every decent person finds cheating and fraud repulsive and offensive. Pride and vanity arouse resentment when they do injury. When people realize they have been duped, they can react impulsively and lethally. Billionaires are superdupers it appears. The Mutuality Model exposed the predatory cabal of excessive wealth. Framed as cheats and frauds, the admiration of the plutocrat class deflated. Resentment may be sufficient to obviate almost any bias.

I would like to see the end of plutocrats without killing them. They are dreadful, really, and should have their fortunes humbled. Ostraka employs the dread of death as a motivating factor; its agents are not so nice. Death is confounding to plutocrats, but not to me. I may be ultrawealthy, but I am no plutocrat. I would have a lot to lose if I wasn’t intent on giving it all away, any way. For me, money has always been a means, not a motivator. I am peculiar that way.

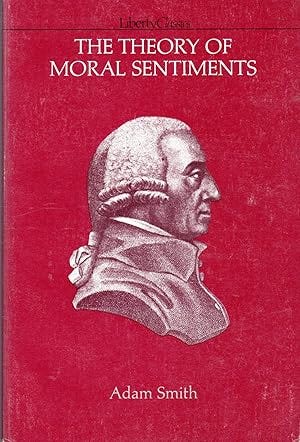

GG: Let’s focus for a moment on ethics and expediency, the subject of your celebrated Essay on Usufructation. You first addressed incentives and ethics at Benefaction, branding ‘beneficence’ so to speak. You were exposed in an undergraduate Honors Reading Seminar to an intense study of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics conducted by a Benedictine monk who fled Korea after WW II, and who completed his studies with the Committee for Social Thought at the University of Chicago. You have referred to him as a provocative mentor, a fertile mind, a man who taught others to think. Yet your social thought and your work product, especially the Mutuality Model, are grounded in the social ethic propounded by Adam Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. How's that?

RS: That was an easy choice; I endorsed prudence over pride as the middle path to a social ethic and moral behavior. Aristotle was a prig, according to the later judgment of the monk who loved the golden mean. The concept of virtue as a mean between extremes is a compelling and enduring conceit. But, Aristotle’s perfect man considered pride the top virtue. His perfect man was a top-dog aristo, one of the few, the few who had the means to seek perfection.

The prudent person, even with imperfections, was Adam Smith’s perfect person. The prudent person believes in transcendent and pragmatic things. The prudent person is serious and earnest about genuine understanding. Not artful, not imposing, not cunning, not arrogant, not pedantic, and not pretentious. Frank and open, truthful in all things, but reticent in most. Smith’s prudent person has a sacred regard for the happiness of neighbors, and would not hurt or disturb them. We think Adam Smith’s perfect prudent person would find MM most hospitable, and appropriate to the circumstances of the day.

GG: With your fortune secure, you developed a data aggregator and an algorithm dubbed Usufruct which, in turn, was the foundation for the Mutuality Model. What were your objectives in this effort?

RS: Usufruct developed and implemented a proprietary technology denominated IED (‘deliberately equitable intelligence’), a sophisticated datamaster, an open-source tool for social analysis, criticism, reckoning, and remediation, designed to explode the prevailing economic exploitation model in favor of a model promoting equitable mutuality, and to maximize beneficence in social relations. The beta analysis led to a startling, existential conclusion: the plutocrat-inheritance class was in fact not sustainable any more and poses a most pernicious threat to all others. The net societal cost of the so-called plutocrat class was not just unconscionable, but more toxic and deadly than lethal pandemic disease or the effect of any series of the worst natural disasters, and getting worse. Recent technological advances compound, accelerate, and magnify the threats to which hoarded wealth exposes us.

Usufruct demonstrated that inequity was approaching a skew so pronounced that hyper civil unrest was imminent. The greatest and most pernicious threat of the greatest concentrations of wealth was to representative, republican, liberal democracies. Excessive wealth threatens freedoms everywhere. Current concentrations of wealth were shown to be correlative to imminent war, pestilence, disease, pollution, and massive human suffering. These inordinate risks invited consideration of decisive incentives and disincentives to curtail the mere fetishism of wealth. The Mutuality Model addressed the opportunity costs and marginal utility associated with hoarded wealth. Exposing the fetish of money and wealth that cloaks the corruption and rigging that privileges the few to equitable scrutiny was key to the science and methodology of the Mutuality Model. The Model promoted the majesty of sharing and public benefaction.

GG: You told us you are about to disappear, so that disgust will not consume you. Your former wife and business partner, Riley Sheridan, collaborated with you on some colossally successful ventures. You were lucky in partnership, and then, so not so lucky. The dissolution of your marriage to Riley was notorious; you have both insisted that betrayals turned you into adversaries for a time. Last week she said you have forgiven each other. Is that true?

RS: I am allergic to bullshit. Betrayal is my nemesis. The truth is, Luc betrayed us both. Riley crushed my heart, but I never wanted to see her suffer. She was duped by Luc, and it was his lying that estranged us both, at different times. We parted when I chose to keep on the path of beneficence over bullshit. I admired her ambition, but then her ambition was married to avarice, and she became for a time a conduit for Luc’s resentments. Luc deeply resented every one of my successes; Riley never did. Riley was easy to forgive. Luc’s resentments are epic; Luc’s pride rivals you-know-who.

Sorry, I have to go now. Thanks. Peace, out.

ON THE PRINCIPLE OF USUFRUCTATION

Thoughts on the Marginal Utility of Plutocrats

Ever a state flourishes when wealth is more equally spread. Francis Bacon

We are a rapacious species. Avarice is idolized. Stewardship is a minority enterprise. The waste and abandon of Easter Island seems to portend our destiny on earth.

Cupidity, Voltaire insisted, is the mother of all crimes. The crime of cupidity impoverishes us. Poverty is the paradox of progress: it persists even where progress prevails.

Nature provides its bounty indiscriminately. Hoarding is a form of theft when things are kept from those who need them by those who do not need them. Many believe that hoarding is the worst crime in the universe, that nothing has value until it is shared or given away.

Hebrew prophets and Christian church fathers found causal links between wealth and poverty: the wealthy few deprive the many poor of the earth’s natural bounty and misappropriate the fruits of their labor, leaving them living always on the brink of ruination. To take the bread of the poor is to take life, to take it by fraud is manslaughter. Hoarders of plutocratic wealth impoverish the spirits of good people, inflict mourning without comfort, take the earth away from the meek, starve all who hunger for justice, slander their critics, and are merciless to the pure of heart.

In our American tradition, Thomas Paine puts the sentiment another way: ‘I care not how affluent some may be, provided that none be miserable in consequence of it.’ Hoarded wealth is a moral betrayal. Hoarding of wealth divorces the world from the common good. We have found that excessive wealth is an imperious encroachment on civic life. Excessive wealth holds the many in perpetual debt and thrall to the few, creating what John Adams called ‘the eternal internal struggle … which has overturned every republic from the beginning of time.’ According to Adams, ‘the great secret of liberty’ is to limit the power and control the passions of the wealthy.

Worse than useless, outsize fortunes are anti-competitive and anti-social. The ultimate issue with excessive, offensive, confiscatory fortunes is that they are a threat, an existential challenge to sovereignty in a modern democracy. They sap sovereignty. They are pernicious to society. They are a form of tyranny. This is now demonstrable.

Isaiah Berlin tells us the central question of politics is the question of obedience and coercion. But plutocrats, by and large, need not obey and cannot be coerced. Ambrose Bierce equated wealth with impunity. Only satire and death seem to save us from the impudence of wealth and power.

Equity does not occur in nature except as a human artifact. Mutuality is the foundation on which equity is constructed. This Essay examines the marginal utility of plutocrats, introducing the Mutuality Model (MM) developed by Usufruct as a tool for social remediation. Equitable social equilibrium is the goal of MM. MM provides a theoretical framework, authoritative data, and a robust model for understanding and addressing the deep structures and persistent threat of excessive wealth and wealth inequity.

The Mutuality Model has revealed deep structures, secret alliances, the web of corruption, and the sinister methods of systemic rigging that favor great fortunes, and especially wealth accumulated over generations. Thomas Piketty tells us, ‘once a fortune is established, the capital grows according to a dynamic of its own, and it can continue to grow at a rapid pace for decades simply because of its size.’ Great fortunes have economic gravity and will compound, even in contractions. Fortunes and the fortunate become impervious to fortune, and extravagantly arrogant.

The paradox of excessive fortunes is that they are seemingly inert, yet they compound spontaneously; that makes them all but unassailable while they grow, and as they grow they become even more destabilizing. They are the greatest impediment to the balance of equities in a healthy modern democracy. Excessive fortunes are unhealthy and unnecessary.

Knowledge, like truth, is liberating, a form of freedom. Civilization is a form of shared, societal knowledge that allows flourishing of the human spirit. Knowledge has a propensity to become known, to become available and useful. The diffusion and sharing of knowledge is, according to Piketty, ‘the public good par excellence.’ It is also, he says, key to the reduction of inequality both within and between countries.

The Mutuality Model was developed as a public, open-source good. MM determines that only radical measures restructuring the social commitments that wealth owes to its actual progenitors can reverse the current illiberal, oligarchical trends producing unprecedented threats to freedom in American society and abroad. Concurrent with Piketty, MM recommends appropriate tax reforms and commitment to global accountability as antidotes to the grave social threat of worldwide oligarchic domination.

1. ETHICS AND EXPEDIENCY

As Professor of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow, Adam Smith lectured on four subjects: natural theology, ethics, justice, and expediency. His lectures on ethics and on expediency each morphed into a seminal, enduring work. Ethics was the subject of Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759. But Smith is best known for the ideas promulgated in his lectures on his fourth lecture topic, expediency. Lecturing on expediency turned Adam Smith into the most renowned economist of all time, and precipitated An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776.

Adam Smith mastered ethics, and then proceeded to master economics: we think he got the order of priorities correct. With Adam Smith, we contend that expediency must have an ethic; economics always implies a moral dimension. Contemporary of Adam Smith, the renowned lexicographer, Samuel Johnson, in his famous Dictionary, defined ‘expediency’ as “fitness; propriety; suitableness to an end.” There must be a fitness to economic structures, apt intentionality, and objectives suitable to beneficent ends.

For Smith, morality was a blend of prudence, justice, and benevolence. Prudence is about self-preservation. Justice is commutative: the rules should apply equally to all, and all should be reasonably secure and free from coercion as a matter of law and authority. Benevolence acts in the interest of others, voluntarily: Smith thinks we are not whole persons unless we are free to express our benevolence toward others. As Adam put it: ‘to restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent, affections constitutes the perfection of human nature; and can alone produce among mankind that harmony of sentiments and passions in which consists their whole grace and propriety.’

We are prudent when looking out for ourselves; justice and beneficence are about looking out for others. Smith elevated beneficence to a sublime, even divine, status. He said that those motivated to act ‘solely from a regard to what is right and fit to be done, from a regard to what is the proper object of esteem and approbation, though these sentiments should never be bestowed upon’ them, can be credited with acting ‘from the most sublime and godlike motive which human nature is even capable of conceiving.’

The Vulgarity of Money

Wealth is insolent. The prophet Isaiah tells us the wealthy build their mansions from the spoils they take from the poor. The wisdom of Tao Te Ching admonishes: wealth and privilege breed insolence and resentment, leaving ruination in their wake. As wealth accumulates, poverty compounds. As long as the ultrawealthy have their way, poverty will always be with us.

When the ancient Greeks thought about wealth, it was as spoils, the product of piracy and war. For the Romans, who spoiled the Western world, given voice by Juvenal, it was more personal:

Here lies the root of most evil: no vice of the human heart

is so often inclined to mix up a dose of poison,

or slip a knife in the ribs, as our unbridled craving

for limitless wealth.

Paul, the chief Christian correspondent, equates avarice and idolatry. Jerome was harsh, and, a child and beneficiary of great privilege himself, asserted: the rich are either dishonest or the heirs of thieves. Sin is required to gain and to keep riches he says, and, wealth robs the wealthy of a sense of value. Aquinas agreed with Boethius: wealth gains value in giving, and only does harm in its hoarding. Dante thought the acquisition of wealth ruined the Church.

Great wealth employs government to erect and protect its dynastic concentrations of wealth. Governments protect concentrations of wealth with great force and enforcement, with formidable legal systems favoring property and ownership. As John Adams says, ‘wealth is secured by public expenses.’ Wealth is the product of human exertion to gratify human needs and desires. The wealthy are the product of systematic extortion of rents on the products of the exertion of others, with the support of government and law, in order to gratify the desires of the wealthy few. Rousseau contends that any good the rich might do is outweighed by the evil done to acquire the wealth. ‘Giving back’ is simply restitution.

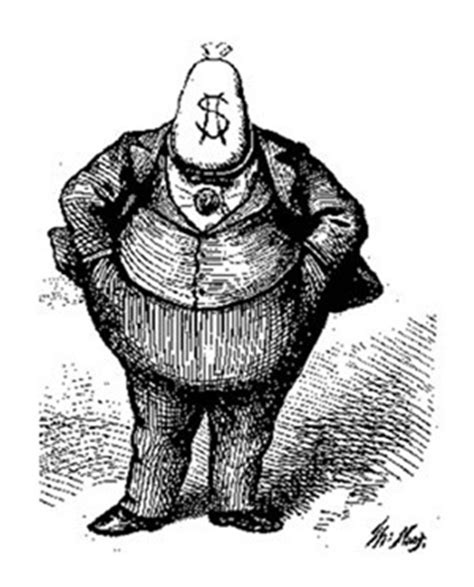

Henry George found the inequities of wealth distribution to be the ‘curse and menace of modern civilization.’ He traced this to the regime of private property in land. Rents divert most of any increase in productive power into the teeming coffers of the wealthy. George said the admiration of wealth comes from the fear of poverty. Wealth demagogues the fear of poverty. ‘Great wealth always supports the party in power, no matter how corrupt it may be,’ according to Henry George. Theodore Roosevelt called this the ‘vulgar tyranny of mere wealth.’

The superrich are owned by their wealth. Their wealth consumes them. Wealth is not content with contentment. Wealth corrupts the minds of the wealthy and makes them lust for power. Wealth exempts the few from the strains and exertions that others must make to sustain life. With the necessities of life secure, wealth privileges the rich with means and special opportunities to achieve personal goals and selfish purposes. Above all, wealth is the formidable means by which the wealthy gain power over others. Our world is subservient to wealth, in bondage to the superrich.

For whose good, the wealth of the world? For hoarders, or for helpers? The wealth of the world is the fund for the flourishing of the human spirit on earth, the common fund that will determine human destiny. Wealth, excessive and inherited, is a social problem, and lies at the root of all political problems. In truth, excessive wealth is a menace. FDR, a great and magnanimous inheritor, in 1935 told Congress that great inheritances of wealth and power have ‘disturbing effects’ on national life. He said, further, ‘The transmission from generation to generation of vast fortunes by will, inheritance, or gift is not consistent with the ideals and sentiments of the American people.’

Marx says social consciousness is formed, or derives from, the economic structure of society, and that the ‘mode of production of material life’ of the moment determines the legal and political structures of society, and conditions social, political, and intellectual life. For Marx, capital represents, or conceals, a social relation. He says value ‘is something purely social.’ He says capital is value looking for accumulation. In commercial exchange, value is objectively attributed to products. Value is a social construct, an objective measure based on labor, or effort.

Seemingly obvious and trivial, analysis of a commodity by Marx ‘brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.’ The mysterious character of a commodity for Marx derives from the objectification of the human effort that produces it, the social relations that it reflects. Marx calls this the ‘fetishism’ that attaches itself to the products of labor; it is a fantasy about relating to things as if their production by human effort has imbued them with a form of life of their own, and thus produces a social relation in the thing. If you collect anything, any type of thing, you know what a fetish is.

Money is magic. Gold is bedazzling. Or so our fetishes make us believe. ‘In its function as measure of value, money serves only in an imaginary or ideal capacity,’ according to Marx. Karl reminds us that when Titus, destroyer of Jerusalem, reproached his father, the Roman Emperor Vespasian, for the vulgarity of imposing taxes on public lavatories, the dad replied: Non olet! (Money has no odor; it does not stink.) Farmers take the inverse view: the waft of manure is ‘the smell of money.’

The ancient Greeks put it succinctly: money is for reckoning. Money is a marker for value, a means for exchange. Money is a social pledge. We use moneygold to relate to one another for exchanges, transactions; they predominate in our daily lives, they define and delimit so many of our social relations. And yet, money makes strangers of us all. For Marx, paper money is a symbol of gold, and thus a symbol of value. As Marx put it: ‘money is the absolutely alienable commodity … the product of a universal alienation.’ This is the riddle of the moneygold fetish.

Harnessing the labor of others is necessary to transform money into capital; capital turns labor into a commodity, just as it objectifies labor in the commodity. Capital formation requires workers, if not slaves, then a free market for labor, what Marx terms ‘the vampire thirst for the living blood of labor.’ Marx talked about ‘the most fundamental right’ sustained by ‘the law of capital’ being the right of equal opportunity for exploitation of the labor force by capitalists. The means of production and subsistence become capital only when ‘they serve at the same time as means of exploitation of, and domination over, the worker.’

Developments in the division of labor derive from what Smith calls a certain propensity in human nature, the ‘propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.’ We are transactional by our very nature, and out of necessity. Smith discerned that the division of labor brings about and accounts for great gains in productivity. The same number of people, with the same amount of effort, are capable of ever-increasing gains in productivity as labor is divided among them. Division of labor brings more focus or expertise to the performance of a discrete element in a process of production. The division of labor makes everyone’s labor substantially more productive. Smith believed the division of labor in a well-governed society fostered the proliferation of innovations in all arts, sciences, and techniques, and delivered benefits throughout society.

The Mutuality Model finds that the division of land is conceptually nearly identical to the division of labor in its beneficial effects and anticipated gains in productivity, but amplifies them materially.

The Irrational Admiration of Wealth

Humans tend to associate or project all sorts of ‘greatness’ on to those who possess great wealth. Smith asserts in The Theory of Moral Sentiments that wealth and greatness induce a kind of hypnotic admiration, even worship, from what Smith refers to as ‘the great mob of mankind.’ Smith elucidates on admiration: it is, he says, ‘approbation heightened by wonder and surprise.’

In fact, Smith says: ‘wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility.’ For perspective, he queries: ‘What can be added to the happiness of the man who is in health, who is out of debt, and has a clear conscience?’ To what end, he asks, are avarice and ambition? To what end, the pursuit of wealth and power and preeminence? To what end if not to care for ourselves and benefit others? Prudence helps us survive; justice keeps us safe from evil deeds; and, beneficence is the noble end or objective for the use of talent, wealth and power.

The world has a fetish for wealth. The glory of wealth is the esteem and deference the world extends to the wealthy along with its admiration. The attention of the world is drawn to, the world looks to, i.e. admires, great wealth and its possessors. With deference come social distance and other advantages for the wealthy. But the admiration is the greatest advantage. The world wants to see itself in the wealthy; even the wretched give their token of admiration. The human psyche is predominantly irrational; that accounts for the world’s fetish for wealth.

Admiration induces the great swell of pride in possessors of great wealth, and thus their arrogance and insolence. Of course, they would concede that the admiration is warranted. Great fortune and pride go together. The proudly, hugely wealthy, Smith opines, ‘wonder at the insolence of human wretchedness, that it should dare to present itself before them, and with the loathsome aspect of its misery presume to disturb the serenity of their happiness.’

Smith wondered at the paradox of obsequiousness to the wealth class arising out of admiration for their vast advantages without any benefit deriving from the sycophancy: ‘We are eager to assist them in completing a system of happiness that approaches so near to perfection; and we desire to serve them for their own sake, without any other recompense but the vanity or the honour of obliging them.’ Smith called this the ‘easy empire over the affections of mankind’ enjoyed by the ultrarich. He described the consequent condescension in this way: ‘the great never look upon their inferiors as their fellow-creatures.’

All this admiration of the rich, said Smith, corrupts our moral sentiments, and leads us to depise and neglect the destitute. In fact, he said, this disposition to admire, almost worship, the rich and powerful, and to despise the poor is ‘the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.’ The great esteem and regard due to wisdom and virtue is attributed rather to those who have contempt for poverty and weakness, on those with contempt for benevolence. The absence of, even contempt for, benevolence is the greatest indictment against excessive wealth.

Adam Smith called conscience the great inmate of the breast, the other I, an impartial spectator, the judge and arbiter of our conduct, the one who ‘shews us the propriety of generosity and the deformity of injustice; the propriety of resigning the greatest interests of our own for the yet greater interests of others; and the deformity of doing the smallest injury to another in order to obtain the greatest benefit to ourselves.’ That person within admonishes ‘that we value ourselves too much and other people too little.’ Adam Smith admonishes that we ought consider ‘the real littleness of ourselves.’ We exuberantly extend that admonition to those who hold great wealth.

Envy and resentment are cousins, always germane to the world’s fetish for great wealth. If you are wealthy and do not seem malevolent, you are credited with benevolence. If you do harm and act in serious bad faith, your condescension and contempt are exposed and envy turns into resentment. Resentment is the most destructive force in society. Resentment brings riot, anarchy, and revolution. Resentment is irrationality rampant.

When the French aristocracy lost their power and privilege to exploit and oppress at the Revolution, they were viewed as worthless parasites preying upon society, deserving of death. Admiration quickly turned to hatred and intolerance.

So much more certain are the effects of resentment than of gratitude. Samuel Johnson

Hannah Arendt, apropos of wealth and resentment, says: ‘neither oppression nor exploitation as such is ever the main cause for resentment; wealth without visible function is much more intolerable because nobody can understand why it should be tolerated.’ Why must those who are oppressed and exploited tolerate such an insult?

Resentment seeks a prompt reckoning on oppressive conduct, an accounting for harm done, incapacitation from doing further harm; resentment seeks expressions of remorse and reformation. Resentment is defensive, a natural expression of a sense of justice and fair dealing. Resentment expressed acts as a deterrent and admonition to bad actors.

Passions aroused by pride are like those aroused by resentment, irascible, not easily restrained. Resentment has a will of its own. Animus and ambition, desire for honors or dread of shame, or the desire for dominance or vengeance are irascible parts of all of us. Likewise, retaliation seems an inherent part of our nature, and society approves of the indignation that follows when evil is done to us by others, and accepts righteous acts of indignation as a defense in every case.

2. CONCENTRATIONS OF WEALTH

The sun, through light, warmth, and photosynthesis, and the earth, with its magnetic shield, mineral properties, and abundance of soils, air, and water, create the conditions that sustain life on the planet. All wealth is produced by the operations of the sun and by human endeavor. Human endeavor includes the acquisition of knowledge and the tradition, the handing down, of experience, education, and expertise; the common inheritance of the species.

As the ages, and students of history, inform us, concentrations of wealth into few, and fewer, households is the most pernicious threat to any democratic order. The prime objective of every healthy democracy must be to devise policy that avoids excessive concentrations of wealth, and to promote equitable distributions that deliver the most good to the most people.

The riches of the few are as baggage loaded on the backs of the many. Roman armies called the baggage they carried impedimenta, an apt term for excessive concentrations of wealth. The sagacious Francis Bacon gives us the gist of the figure (we substitute ‘the public good’ for Bacon’s ‘virtue’): ‘I cannot call riches better than the baggage of virtue. The Roman word is better, impedimenta. For as the baggage is to an army, so is riches to virtue. It cannot be spared nor left behind, but it hindereth the march; yea, and the care of it sometimes loseth or disturbeth the victory. Of great riches there is no real use, except it be in the distribution; the rest is but conceit.’ (Emphasis added.)

On earth, the house always wins; it is rigged to win. The very rich never lose; their perennial gain is all but guaranteed. It is axiomatic to economists that more than half the people who ever lived, to this day, owned virtually nothing. The top tenth have always owned or controlled the most and the best of what there is. They are the owners of ‘capital’; capital is concentrated wealth. Capital is privileged by law and custom to deliver and enjoy a ‘return’. Capital seizes the value of the past, uses that to dominate the present, and thereby holds ownership of the future in fee simple.

The Mutuality Model performs the revaluation of all asset holdings and valuations.

Oligarchy

Ronald Syme, that dean of historians of Rome, that consummate scholar of the Roman Revolution, and that especially perspicacious student of the Roman ruling class, asseverates that ‘oligarchy is a permanent factor in human history, open or concealed.’ He found oligarchy of government to be the dominant theme of political history; it was the binding link between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. He said that Rome ‘annexes primordial value’ in the study of oligarchy. Syme admonishes: ‘It is something real and tangible, whatever may be the name or theory of the constitution. In all ages, whatever the form and name of government, be it monarchy, republic, or democracy, an oligarchy lurks behind the façade.’

Philosophers tell us the study of history establishes the iron law of oligarchy. Historians tell us that no one has yet discovered any exception to the law.

Primogeniture

Dr. Johnson sarcastically expressed the societal benefit to be found in primogeniture: ‘it makes but one fool in a family.’ Primogeniture was a customary legal right of inheritance in English common law giving to a ‘legitimate’ firstborn male child the parents’ entire estate, excluding all others, including siblings. Primogenture was about maintaining dynastic concentrations of wealth and power through the generations, attempting perpetuity. In most cases inherited land was ‘entailed’ to prevent diminution from generation to generation. The fee tail or entail was a dedicated tyranny, a form of trust established by a deed and enforced in common law courts: the deed created a prohibition on selling or devising the land, prompting the land always to pass intact to an heir. Governing beyond the grave, is what Thomas Paine called primogeniture, ‘a law against every law of nature;’ he said it was vain and presumptuous, ‘the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies.’

Notwithstanding the contention of Adam Smith that ‘all families are equally ancient,’ oppressive societies are historically inheritance societies; those characterized and dominated by inherited wealth and an hereditary, oligarchic top class. Primogeniture, the most oppressive feature to be found in some inheritance societies, became abhorrent to many Enlightenment thinkers. In the Revolution of 1789, a colossal abolition of oppressive, biased legal structures, the French bourgeois levelled the aristos to a position of relative legal equality with aid of the guillotine. The abolition of primogeniture in America in the nineteenth century, and in England, only in the 1920s, liberated markets for real property and other transactions finally allowing for judgments of best uses by those living and breathing.

The antithesis of primogeniture in law is ‘partitive descent’, where property is apportioned among heirs. The preference for partitive descent developed in the American colonies, and was catalysed by Jefferson’s direct attack on primogeniture in 1776, which many consider to have precipitated the abolition through the ensuing decades. Thomas Jefferson famously said, ‘The Earth belongs to the living,’ (excepting, of course, the living belonging to him).

The Rule Against Perpetuities

The contrarian Byzantine bishop, John Chrysostom, characterized wealth as ephemeral: ‘a vain shadow, a dissolving smoke, a flower of grass.’ Is it not rather that it is wealth that remains, endures? It is the wealthy who, passing and dissolving like withered grass into dust, are no more than vain shadows of the wealth they enjoyed and passed on.

Like its mortal possessors, wealth wants immortality. In wealth terms, that is called perpetuity. At common law in England in the seventeenth century, a rule against perpetuities developed to prevent the enforcement of legal instruments purporting to exert control over property beyond the life of any person living at the time the instrument was executed. Such instruments, like primogeniture, had become devices for securing dynastic wealth, undiminished, through generations. The American rule was stated 150 years ago as follows: No interest is good unless it must vest, if at all, not later than twenty-one years after some life in being at the creation of the interest.

The rule means to curtail excessive accumulations by limiting future control by a ‘dead hand’ (mortmain) to a finite, determinate period. The rule against perpetuities is related to other rules against unreasonable restraints on the transfer of property. Probably by design, the rule is notoriously obscure, and obtuse, and confounding in its application: e.g., since a 1961 ruling by the California Supreme Court, it is not malpractice for an experienced attorney to inadvertently violate the rule. Judicial fictions, like ‘the fertile octogenarian’, have been devised to extenuate the rule, always favoring the endurance of dynastic wealth. Were laws not originally devised to privilege wealth? Was our Constitution not originally devised to secure property?

Corporations are considered at law to exist indefinitely, perpetually. They limit liability and can last forever as interests are bought and sold. Corporate and partnership ownerships are transferable and readily traded in markets. Virtually all of the largest fortunes are portfolios of shares of stock and partnerships. Business and financial assets always constitute the bulk of the wealth of the wealthiest. They prefer perpetuity.

When the income tax was added to the U.S. Constitution, J.D. Rockefeller pioneered a novel form of perpetuity by way of characterizing fantastic dynastic holdings as charitable when parked in tax exempt ‘foundations’ controlled by Rockefeller and the natural objects of his bounty through the generations. There is no rule against perpetuities for foundational wealth. Private foundations are the modern entails; a superlative form of legitimate wealth concentration and preservation. Purely private foundations are virtually indistinguishable from those few that do actual charity. Most often, foundations pursue or protect peculiar private interests, public interests being only ancillary. Private foundations are mostly vehicles for retaining family control of the voting stock of publicly traded corporations. MM is the agent of exposure for any measure of public interest achieved or detriment incurred by corporations and foundations.

Breakneck Growth of Ultra Incomes

Thomas Piketty reported the discovery of vertiginous growth of incomes of the top 1 percent since the 1970s and 1980s: ‘When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income, as it did in the nineteenth century and seems quite likely to do again in the twenty first, capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based.’

Inherited wealth tends to grow faster than output and income, according to Piketty, and people with inherited wealth need to save only a portion of their income from capital to see that capital grow more quickly than the economy as a whole. He warns that this dominance of inherited wealth tends to concentrate capital at inordinately high levels.

The past devours the future because, according to Piketty, the rapid, unparalleld growth of inherited wealth is virtually automatic and, ‘almost inevitably this tends to give lasting, disproportionate importance to inequalities created in the past.’ MM has been designed to identify deep structural remediations to substantially ameliorate this pernicious, systemic, enduring bias. Solutions are identified and can be implemented with open algorithmic integrity. Piketty reports on and analyses a globalized financial capitalism, and the ‘worrisome dynamics of global capital concentration.’ MM is the tool designed for application of global controls.

Karl Marx thought that accumulations of capital were inevitably consolidated and became ever more concentrated. He may have failed to imagine the countervailing forces that have become evident in retrospect, but he had a deep intuitive grasp of the perverse, destabilizing fact that the more wealth you control, the richer you will get, and faster, compared to those with less. The odds always favor the house, and you are the house when you reside at the top of the wealth heap. Das Kapital is a study of the accumulation of capital, finding that more means less: the rate at which you gain diminishes as capital increases and eventually fails, and gains become relatively marginal, negligible.

America has reached a point where the historical, compounding effects of high concentrations of capital have developed such extreme inequalities and inequities between the capital class and modern proles that it threatens imminent, severe social and economic dislocations.

The super wealthy are never contented with contentment. They do not know when to stop; they take for the sake of taking. They gravitate toward the extravagant and the excessive. They are a drag on society and its economies. MM finds that no social good derives from vast inheritance, closely held. In fact, excessive concentration of wealth can be likened to pernicious constipation. Excessive concentrations of wealth inhibit social mobility and cohesion, and choke economic activity.

Shocks to Wealth

Historically, wealth is dynastic, not dynamic; dynamic only in the sense that the labor product of others produces the dynastic income and accruals that flow to the enjoyment of the wealth class. Historically, wealth tends to concentrate. We are all acquisitive creatures; many of us are greedy, some predatory and malignant. But as wealth is allowed to concentrate in excessive amounts in a modern democratic society, income inequality evolves into intolerable social inequities and social conflict.

War, its shocks, its chaos, its wanton destruction, is the great leveler of fortunes. Also a wonderful producer and promoter of the inordinate, predatory, profiteering fortunes of certain survivors. The major wars of the twentieth century vastly reduced the inequities that preceeded. Decimations like the Black Death also tend to such levelling. Decimations are indiscriminate and deadly. They leave a wake of destruction like a tornado or a hurricane. Unfortunately, absent economic or political shock, the rich get richer and equities diverge and dissipate toward entropy, until somebody starts a war.

There is no sure or easy path to social equity; incremental achievements get beaten back or repealed, consensus can be ephemeral even when achieved; only shock and awe seem to reset the balance of equities in society.

The Mutuality Model demonstrates that war results from identifiable imbalances predominating in wealth maldistribution, and establishes a compelling set of rationales for outlawing outsize fortunes to obviate the predatory threat correlated to extensive, offensive fortunes. We believe MM is a rival to war for producing conditions re-setting and balancing social equities. There is a strategic role for controlled shocks with various beneficent objectives.

3. RENT-SEEKING

Rent-seeking is making money while you sleep!

Adam Smith categorized income in three basic forms: wages, profits, and economic rents (control of real estate or natural resources). Rent-seeking is distinguished from profit-seeking, where the parties enter into a transaction seeking mutual consideration in the form of benefit or gain. Profit is a return on the investment of time (labor) or treasure (capital), whereas rent-seeking is considered profiteering because it exploits and manipulates government, political, and social institutions for financial gain from wealth transfers lacking traditional contract consideration, often in the form of subsidies, exemptions, licenses, sweetheart deals, and even monopolies, with little or no cost associated. Rent-seeking is confiscatory income. Rent-seekers are called rentiers.

Capital consists of assets with exchange value in a market, the sum of which provide the funds available to stimulate and engender production in any society. Capital, always risk-oriented and entrepreneurial in early accumulations, inevitably morphs in its growth and maturity into rents. According to Piketty, ‘that is its vocation, its logical destination.’

Rent-seeking takes substantial value, offering or producing virtually nothing of value in return, at the same time that it inflicts appreciable costs on society. Rent-seeking is entirely corrupting. Rent-seekers are the rats with the run of the granary. The most pernicious and corrupting means employed by rent-seekers is referred to as agency capture, or regulatory capture. The rent-seeker is the parasite, the agency is the host. The successful rent-seeker in such a capture gains obvious and innumerable advantages including the advantage of disadvantaging competitors not participating in the corruption.

Like its illegitimate child, bid-rigging, rent-seeking is a mockery of the notion of competition and free enterprise. It has been the subject of serious academic study and analysis for the last fifty years, after publication of a couple of seminal papers on the subject. One of those papers, authored by Gordon Tullock, articulated the paradox of rent-seeking: substantial gains come without risk and with negligible cost. But, since when is success through corruption paradoxical; cheaters always have the advantage, just as stealing is more efficient than earning.

Rent-seeking produces no social good and is in fact counterproductive and malign. There is no equity in rent-seeking. Yet, for all of recorded time, rent-seekers and holders of excessive fortunes appropriate a considerable portion of GNP while they sleep.

Wealth is Confiscatory

Wealth is confiscatory; it takes what justly belongs to others. Wealth is greedy, grasping, and exceedingly immoderate. Wealth desires pleasure, riches, and power without limit. Excessive wealth exceeds even greed; pride is the only motivator of great wealth.

Pride is a spiteful master. Aristotle called pride the crown of the virtues, said it is concerned with great things and implies greatness. When it comes to pride, Jesus represents the opposing perspective, the great divide. In the Christian cosmos, Satan’s blasphemy was pride and insolent rebellion. Augustine calls pride a darkness, the craving for undue praise. Or, as Shakespeare puts it in the words of Agamemnon in Troilus and Cressida:

He that is proud eats up himself: pride is

his own glass, his own trumpet, his own chronicle;

and whatever praises itself but in the deed, devours

the deed in the praise.

Spinoza says pride is the imagination of a person thinking too much of that person’s self. Superior fortune engenders pride, and pride in turn engenders insult and contempt. Pride gloats: what is the next best thing to being admitted to medical school? Finding out your best friend wasn’t. Pride diminishes and has contempt for the lives of others. The poet Kenneth Rexroth says pride has a prodigious family: arrogance, rashness, overconfidence, presumption, contempt, cruelty, anger, lust, and carelessness. Pride also has progeny: birthrights, dynastic inheritance, and privileged entitlement.

Economic status in developed countries generally conforms to a ratio with 50% at the bottom, 40% in the middle, and 10% at the top. Piketty says that ‘in every society, even the most egalitarian, the upper decile is truly a world unto itself.’ And at the top of the top decile, is the exorbitantly wealthy and dominant 1%, accompanied by the remaining 9% who are simply the well-to-do wealthy. Social inequities are exposed and can be studied, analyzed, indexed, and remedied most expediently with focus on the tops, 10 and 1.

Exploitation, Predation, and Inequity

Rent-seeking is a prime driver producing conditions of extreme inequality and social conflict. Rent-seeking is exploitation, rampant. Rent-seeking opportunities are available only to capital. Only the wealthy few are privileged to enjoy access to the most lucrative rent-seeking opportunities. Rent-seeking is the preferred occupation of billionaires. The billionaire class is the rentier class.

Capitalism equals exploitation. To Marx, exploitation is the name for the share of the production of others taken by capitalists. Capital exploits weakness and death, poverty and famine, corruption and foolishness, fear of poverty, and the will-to-live. Bacon tells us that even ‘accidents conduce much to fortune.’ He goes on to say, ‘no man prospers so suddenly as by others’ errors.’ The folly of one brings fortune to another.

Top dog capitalists are top dog predators. In nature, predators target the halt and the lame, the weak and the vulnerable. Instinct for identifying prey, not intelligence, mostly inform capital predations. We concur with Bacon thus: predators have the greatest advantage; predators perceive and prey upon the weakness and vulnerability of others; and, their minds are consumed with calculation and gain and are otherwise dull and distracted.

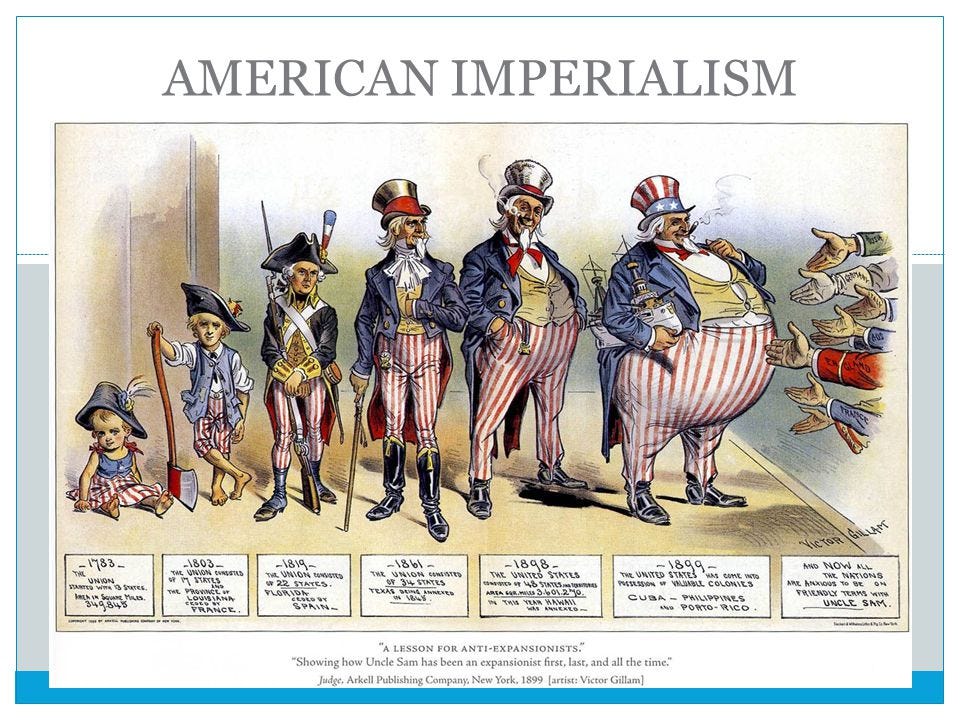

Imperialism: Global Rent-Seeking by Nation States

Power is like a hot gas that must expand, or the tiny ice crystals that will crack a boulder, and level a mountain. Power wants more power, then wants more power. Power has leverage; it is coercive. Power is adamant. Wealth and power are conjoined twins. Wealth and power hate rivals. Wealth and power seek imperium. All capitalists are imperialists at heart. Every business wants to be a monopoly.

Roman imperium was the supreme administrative power, involving political hegemony exercised through military command joined with awesome judicial authority regarding the interpretation and execution of the laws (including the infliction of the death penalty) which belonged to Roman consuls, military tribunes, and dictators.

Polybius wrote to offer explanation for how Rome gained such phenomenal supremacy in such a short time. He gave serious study from an ancient perspective to the success of the Roman system of government which, in about fifty years, in an unparalleled historical achievement, extended its rule to ‘almost the whole of the inhabited world.’ Polybius asserts that this did not happen by chance. On the contrary, he says, Rome was the school for such a great enterprise, and pursuit of absolute dominion was both the Romans’ intended goal and their consummate achievement. Rome was the school of imperium, the school of dominion, the school of tyranny. We are yet to take the proper object lesson.

According to Thucydides, pity, sentiment, and indulgence are kryptonite to imperial power. Gibbon says the history of empire is the history of misery: ‘there is nothing perhaps more adverse to nature and reason than to hold in obedience remote countries and foreign nations, in opposition to their inclination and interest.’ As Edmund Burke reminds us, ‘all empires have been cemented in blood.’ Overwhelming force is required to gain and keep an empire. The logic of empire is brutal and unforgiving. The logic of empire is the logic of capital, and it is a logic without conscience. It is the logic of insatiable greed and accumulation.

Tacitus gives a vanquished chieftan the words to express a thumping denunciation of imperial conquest: he calls empire, in fact, murder and rapine and profit. Indeed, as George Orwell reminds us, ‘an empire is primarily a money-making concern.’ Empires are tyrannical, rapacious, oligarchic systems designed to extract wealth, rents, and toil from subjects. Subjects are just an asset in empires, devices for extracting surplus production and profit.

Published the year after the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588, Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations of the English Nation was an invitation to the English people to adopt imperial pretensions. Imperialism is not as much about maps as it is about markets. In 1902 political economist J.A. Hobson authored a most popular and influential study of the British Empire drawing the obvious conclusion that the aim of empire is exploitation; his famous dictum: ‘finance is the governor of the imperial engine.’

Lenin asserted in 1916 that imperialism is the highest stage of capitalism, predicting the fall of empires as prelude to the implosion of capitalism. The word imperialism had come into the English language about fifty years before that, used to criticize some French aggression.

Lenin described a process whereby free competition among capitalists generally results in capitalist monopolies. He said that imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism and that monopoly is the transition from capitalism to ‘a higher system.’ Lenin’s final word on imperialism includes, as we might expect, harsh censure of the bourgeoisie: ‘monopolies, oligarchy, the striving for domination instead of striving for liberty, the exploitation of an increasing number of small or weak nations by a handful of the richest or most powerful nations – all these have given birth to those distinctive characteristics of imperialism which compel us to define it as parasitic or decaying capitalism. More and more prominently there emerges, as one of the tendencies of imperialism, the creation of the ‘rentier state,’ the usurer state.’

Chalmers Johnson says that Marx and Lenin were wrong: he inverts their logic and says that, ‘It is not the contradictions of capitalism that lead to imperialism but imperialism that breeds some of the most important contradictions of capitalism. When these contradictions ripen, as they must, they create devastating economic crises.’

Capitalism is premised on belief in the cardinal rule of constant economic growth. Capitalists worked to make that the law, at home and abroad. According to Hannah Arendt, expansion is the ultimate political goal of foreign policy: ‘expansion as a permanent and supreme aim of politics is the central political idea of imperialism.’ She contends that the bourgeoisie was ‘politically emancipated by imperialism.’

Arendt says the bourgeoisie’s political device is power for the sake of power, just as the imperialists’ drive is expansion to facilitate further expansion. These are entirely totalitarian conceits. The bourgeoisie sees only private interest in politics, economics, and society. Arendt says their political philosophy is inherently totalitarian in that they are blind and insensitive to social interests that do not serve, promote, or conform to their private interests.

Hobbes, says Hannah, is the only significant philosopher to whom the bourgeoisie has a right and exclusive claim. For Hobbes, the singular objective of a Commonwealth is to accumulate power. For Hobbes, men have equality in their innate struggle for power. That equality is found in the fact that each man has, by nature, the power to kill another. Guile is an antidote to weakness, he asserts. All are insecure. They live in continual fear. The danger of violent death is pervasive and persistent. Hobbes insists that the lives of men are, ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.’ Men are driven by a fear of imminent violent death, and ‘a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceases only in death.’ The perpetual desire for power over others.

The state of nature precedes the birth of Hobbes’s Leviathan, where war is the natural state, and every man is adverse to every other in an essential way. All feel a need or desire for the rule of the state, the Leviathan. For Hobbes, sovereignty is tyranny; it is rule by might, and, by extension, by the mighty. Hobbes boasted of his pride in admitting his adulation for this tyranny.

“By art is created that great Leviathan called a common-wealth, or state, (in Latin civitas) which is but an artificial man; though of greater stature and strength than the natural, for whose protection and defense it was intended; and in which, the sovereignty is an artificial soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body.” Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes was an idolator: he idolized power and success. He proudly endorsed the power of control in a monopoly that permits price-fixing and the manipulation of supply and demand for the sole advantage of the monopolist.

Imperialism is all about domination and exploitation, though it will cloak itself in virtue, progress, and national security to obscure its base designs. Dominance and submission are the frame of imperialism and oligarchy. Militarism and imperialism are indistinguishable, greedy, omnivorous forms of domination. If we follow the thought of John Hobson, the patriotism of imperialists is a paradox because they are parasites upon that patriotism. Imperialism and militarism eventually overtake the defenses liberty has against tyranny.

In general terms nothing opposes the prosperity and freedom of men as much as great empires. Alexis de Tocqueville

Most historians would agree that democracy and empire are ultimately incompatible, just as democracy and tyranny are incompatible. Democracies that acquire empires gain pride and wealth, and put at risk and usually lose domestic liberties. Empire abroad induces despotism on the home front. Chalmers Johnson says American empire is hopelessly contradictory and hypocritical, and especially unstable. It suffers the centrifugal dynamics Johnson says that always apply to empires: overreach, isolation, consolidation of the opposition, and capital and market collapse, i.e., bankruptcy.

Pernicious Petroleum Rents

Piketty warns us that ‘petroleum rents might well enable the oil states to buy the rest of the planet (or much of it) and to live on the rents of their accumulated capital.’ That is not hyperbolic. The oil states kind of figured out capitalism in the 1970s. But the race for ultimate dominance is on. Piketty is not being rhetorical when he asks, ‘Will the world in 2050 or 2100 be owned by traders, top managers, and the superrich, or will it belong to the oil-producing countries or the Bank of China?’ Will fossil fuels fuel the market for ultimate dominance? Who ultimately dominated on Easter Island?

The rate at which these forces approach the objective of ultimate dominance is fast and is accelerating. Piketty thinks it may be approaching the kind of skew and imbalance making revolution likely to occur ‘unless some particularly effective repressive apparatus exists to keep it from happening.’

If that is not ominous enough, Piketty sees a most credible danger in what he terms ‘an oligarchic type of divergence – a process in which the rich countries would come to be owned by their own billionaires.’ He says the process is already well underway.

We believe the Mutuality Model is an effective repressive apparatus for reversing the oligarchic divergence. We invite Piketty to concur.

4. THE MARGINAL UTILITY OF PLUTOCRATS

A billion is never enough! Like the inner voice of Henderson the Rain King, the incessant inner refrain of billionaires is, ‘I want! I want! I want!’ They always want more. They are speaking the native language of their capital. Capital is desperate, under compulsion, to grow, to accumulate, to dominate. To grow, capital must produce income, i.e., it must find means to stimulate and capture returns from the useful productions of others.

All goods and services have some economic ‘utility’, that is, some useful satisfaction or benefit is gained by consuming or acquiring a product, a good, or a service. The economic utility of any good or service is subject to change. The utility of a good or service will change when there is an increase in the consumption of the good or service: that change is referred to as ‘marginal utility’, an incremental change, increasingly small.

The marginal utility or productivity of capital is determined by the additional value produced by application of an additional unit of capital. As any stock of capital increases, the marginal productivity of that capital stock decreases. There is a decreasing yield or return to be expected from each unit of capital acquired. There is more utility yielded by the first unit than from the next, even less from the next. That is the law of diminishing marginal utility. The greater the amount of capital, the greater the reduction in yield is to be expected. The law of diminishing marginal utility is similar to the law of diminishing returns. Saturation returns a value of zero in terms of marginal productivity.

The value of any good or service correlates directly to scarcity. We have ancient wisdom from Aristotle in his Politics admonishing us that the uses of goods have a limit; useful things, when there are too many or too much, do harm or become useless. The utility of capital becomes marginal to the point of uselessness, and harmful, in excess.

I must drink water every day to live. If I drink too much water at one time, the water will kill me. I have exceeded the maximum total utility of the water. There, the marginal utility of another drink of water equals zero and crosses into negative territory. Maximum total utility occurs when marginal utility equals zero. Negative marginal utility is a thing, a very bad thing, that follows on maximum total utility.

The Utility Paradox

What social price do we pay to sustain and protect generational wealth? What value to society is a billionaire? What detriment? What is the cost to society to create a billionaire? Is it exorbitant? Can there be too many billionaires? How many is too many? How might we determine that? We don’t need billionaires like we need water. Diamonds have important uses, but we could live without them. What would we lose if no one controlled vast, hoarded wealth? The Mutuality Model predicts vast societal benefits. We may wish to tolerate plutocrats, but they are unnecessary. We may not wish to tolerate the disequilibrium and inequity that corrodes society in favor of hoarded wealth.

Because we are largely irrational creatures, reason accounting for just a small slice of our psyche, we trade and make judgments more through perception and bias than we do through reasoned analysis and intricate calculations. We can all be duped, defrauded, deceived and misled by sharp practice. We can be convinced to value worthless, even harmful, things. Propaganda, biased rhetoric, and shameless sophistry gain great purchase among us.

Adam Smith, writing in the shadow of classical and later authors who opined on the matter, gave us the classic conception of the contradiction expressed in the ‘paradox of value’. Smith used the figures of diamonds and water to explicate the paradox. Water, plentiful, abundantly useful, and necessary for survival, is cheap in comparison to diamonds which, in Smith’s time, were scarce, largely useless, with no vital attribute.

Smith distinguished between use value and exchange or relative value: this contrasts the value a thing has to a user or consumer to the value it might have to a seller. He says the most useful things frequently have no exchange value, no buyers; water, in his illustration (things have changed much in recent decades). But things which command the highest prices in markets are frequently relatively useless things, like diamonds for Smith’s contemporaries. This is Smith’s paradox of water and diamonds, his illustration of the paradox of value. In Adam Smith’s time, water wouldn’t buy you a beer, but diamonds would buy you a brewery. It seems like a paradox that tracks the split in our psyches, rational and irrational; we can value the priceless things that are necessary to keep us alive, but cannot be sold, at the same time that we can attribute enormous monetary value to relatively, essentially, useless things. We are the paradoxical species: ask any economist. We are, all of us, living, breathing contradictions.