Divination, Dreams and Portents

Divination satisfies a characteristic human need

Excerpted from A Whirld of Words: A Reader’s Commonplace Dictionary.

You will find the WORKS CITED below.

divination

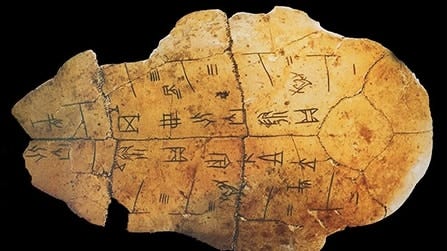

divining the future by the colorations, cracks, and other features of animal shoulder blades is a human custom widespread and venerable, called scapulimancy, or omoplatoscopy; pyro-scapulimancy when the diviner created omen cracks in the bone by roasting or burning; the attempt to seek reassurance about the future in burn cracks made in animal shoulder bones satisfied a characteristic human need for well over five thousand years

(Keightley 1978) p. 3, 5

Shang divination served to regulate and idealize the social and moral order

(Keightley 2000) p. 19

yarrow-stalk divination, the fancies that wove themselves round the property of the numbers that played important parts in this system of divination, is essentially a development of primitive omen-taking by 'odds' and 'evens'

(Laozi 1958) p. 112

the tortoise and the yarrow-stalks represent two methods of divination. The first consisted in heating the carapace of a tortoise and reading the cracks that appeared; the second, in shuffling stalks of the Siberian milfoil

(Shi and Waley 1960) p. 150

there are two major motivations in divination – the first is the desire to understand the operations of the natural and supernatural forces in the environment so that one's own actions may be in accord with them, thus producing favorable results; the second is the filial responsibility to keep in touch with deceased family members so that one may do whatever mortals can do to help them in the nether world

(Thompson 1989) p. 20

none but the fools believe in oracles, forsaking their own judgment

Orestes (Aeschylus et al. 1990) p. 592

the liver is the seat of divination; no man, when in his wits, attains prophetic truth and inspiration

(Plato 1990) p. 467

etrusca disciplina, the religious sphere of divination which the Romans imported from their neighbors

(Hooker 1990) p. 330

what leads to frequent use of divination? Cowardice, the dread of what will happen

(Epictetus 1990) p. 137

this mode of divination, by accepting as an omen the first sacred words which in particular circumstances should be presented to the eye or ear, was derived from the Pagans; and the Psalter or Bible was substituted to the poems of Homer and Virgil. From the fourth to the fourteenth century, these sortes sanctorum, as they are styled, were repeatedly condemned by the decrees of councils, and repeatedly practiced by kings, bishops, and saints

(Gibbon 1983) v. 2, p. 397

with the exception of some philosophers, nobody in antiquity questioned the truth of oracles, ominous dreams, and portents foreshadowing future events. Since the ancients generally believed in a predestined fate, future events and destinies were only slightly hidden from them under a veil which an inspired mind could penetrate. It was therefore a common feature of Greek and Roman life to make decisions dependent on an inquiry into fate. This ancient trust in divination had never lost its reputation until the church uprooted it

(Löwith 1949) p. 10

acts of divination – the acts that determine undetected latent sense are properly so called

(Kermode 1979) p. 4

divination was an important and integral element in all ancient religions. If we limit ourselves to the Greek and Roman world, the range of possibilities that the art of prognostication offered to persons who wanted to know what the gods had in store for them or demanded from them, was immense. In the official and in the private sphere there was a bewildering variety of choices. One could resort to official oracles, to interpreters of dreams, to astrologers, to augurers (who practiced divination on the basis of the flight or the sound of birds), to haruspices (interpreters of the entrails of a victim offered in sacrifice), even to persons who had mastered the details of hepatoscopy (the specialized inspection of the liver of the sacrificial animal) or of teratology (the interpretation of monstra), to engastrimythoi (channelers, or persons possessed by a divine mantic spirit that resided in their body); further there was latromancy (obtaining medical advice via incubation); necromancy (consulting the dead), lekanomancy (looking into a dish), catoptromancy (looking into a mirror), alektryonomancy (observing the behavior of sacred chickens), chiromancy (divination by palmistry), geomancy (divination by earth), hydromancy (divination by water), aeromancy (divination by air), pyromancy (divination by fire), libanomancy (observing the direction of the smoke of incense), aleuromancy (divination from flour), obscopy (divination from eggs), omoplatoscopy (observing the shoulder blades of sacrificial animals), sphondylomancy (divination from the movements of a spindle), coscinomancy (divination by means of a sieve), rhabdomancy (divination by a wand), cledonomancy (the interpretation of auditive omens, e.g. sneezing and casual remarks), and cleromancy (prognostication, or rather problem-solving, by means of the drawing of lots [sortilegium] or the casting of dice [astragalomancy] or other randomizing practices

(Rutgers 1998) p. 143

Constantine began to regulate the art of divination. Constantine drew a distinction between public and private divination. The latter was prohibited. A haruspex who entered a private house for purposes of divination was to be burned alive, while the man who invited him was to lose his property and to be exiled to an island. Public divination, however, Constantine allowed as a relic of the past

(Barnes 1981) p. 52

astrology

the period from 300 BC to approximately 150 BC is considered to be the formative period for the development of astrology in Western civilization. During that time the Babylonian theories of astrology were greatly revamped and expanded by Hellenistic concepts and philosophy, and Aristotelian science was applied to explain the nature of the astrological influences and their effects. For these reasons scholars call this form of astral divination Greek astrology even though it had some of its origins in Babylonia

(Molnar 1999) p. 39

auspices

a form of divination based on the observation of birds and used to determine whether the gods approved or disapproved of a proposed action. Roman magistrates took the auspices before every major decision affecting the Roman people: elections, political assemblies, and battles. Auspices originally were taken from the flight patterns of birds, but by the historical period they were normally based on the eating patterns of chickens that were kept on hand for this purpose: it was a good omen if they ate greedily, and a bad omen if they refused their food

(Suetonius 2007) p. 311

auspicium

a term used by the Romans for certain types of divination, particularly from birds, designed to ascertain the pleasure or displeasure of the gods towards matters in hand

(Hammond and Scullard 1970)

runes

Tacitus famously describes the use of runes, or something like them, in divination; runes were sufficiently well known for Ulfila's Gothic alphabet to borrow some letters from the runic futhark, and were originally devised for engravings on wood

(Bowman and Woolf 1994) p. 178

signs

ancient myths report that on the day when Ts'ang Chieh, inspired by divinatory figures, traced the first signs, Heaven and Earth trembled, and gods and demons wept. Thus, the quasi-sacred veneration devoted to the ideographic writing itself in China. Signs incised upon the shells of tortoises, upon the bones of oxen. Signs borne upon bronze vessels, sacred and mundane. Divinatory or utilitarian, these signs are manifest first of all as tracings, emblems, fixed attitudes, visualized rhythms. Each sign, independent of sound and invariable, forms a unity of itself, maintaining the potential of its own sovereignty and thus the potential to endure. From its beginning the Chinese writing system has refused to be simply a support for the spoken language. That system of writing has engendered a profoundly original poetic language. Poetic language proposes to explore the mystery of the Universe by means of signs. The earliest known specimens of Chinese writing are divinatory texts carved on bones and shells. Later inscriptions, cast in bronze vessels, are also extant. Both date from the Shang dynasty (eighteenth to eleventh centuries BC). Man, heaven, and earth constitute, for the Chinese, the Three Talents (san-ts'ai); these participate in a relationship of both correspondence and complementarity. The role of man consists not only of 'fitting out' the universe, but of interiorizing all things, in recreating them so as to rediscover his own place within. In this process of 'co-creation', the central element, with regard to literature, is the notion of wen. This term is found in many later combinations signing language, style, literature, civilization, and so forth. Originally it designated the footprints of animals or the veins of wood and stone, the set of harmonious or rhythmic 'strokes' by which nature signifies. It is in the image of these natural signs that the linguistic signs were created, and these are similarly called wen. The double nature of wen constitutes an authority through which man may come to understand the mystery of nature, and thereby his own nature. A masterpiece is that which restores the secret relationships between things, and the breath that animates them as well

(Cheng and Seaton 1982) p. x, xii, 3, 213

the gods communicate directly with few people, and do so infrequently, whereas most people receive only signs, which is why divination has been developed

(Plutarch 1992) p. 347

taurobolium

the Taurobolia became fashionable in the time of the Antonines

(Gibbon 1983) v. 1, p. 486

the taurobolium is by far the most notorious ritual celebrated by the last pagans of Rome, thanks to a vivid account by Prudentius. 'In order to be made holy, the high priest goes down into a trench dug deep in the ground wearing an extravagant headband, his temples bound with fillets for the occasion and his hair clasped with a golden crown, while his silken robe is held up with the Gabine girdle. Above him they lay planks to make a stage, leaving the timber-structure open, with spaces between; and then they cut and bore through the floor, perforating the wood in many places with a sharp-pointed tool so that it had a great number of little openings. Hither is led a great bull with a grim, shaggy brow, wreathed with garlands of flowers about his shoulders and encircling his horns, while the victim's brow glitters with gold, the sheen of the plates tinging his rough hair. When the beast for sacrifice has been stationed here, they cut his breast open with a consecrated hunting spear and the great wound disgorges a stream of hot blood, pouring on the plank-bridge below a steaming river which spreads billowing out. Then through the many ways afforded by the thousand chinks it passes in a shower, dripping a foul rain, and the priest in the pit below catches it, holding his filthy head to meet every drop and getting his robe and his whole body covered with corruption. The paltry blood of the dead ox has washed him while he was ensconced in a loathsome hole in the ground'

(Cameron 2011) p. 159

wisdom

wisdom is the faculty which commands all the disciplines by which we acquire all the sciences and arts that make up humanity. Wisdom among the gentiles began with the Muse, defined by Homer in a golden passage of the Odyssey as 'knowledge of good and evil', and later called divination. The Muse must have been properly at first the science of divining by auspices. The word wisdom came to mean knowledge of natural divine things; that is, metaphysics, called for that reason divine science, which, seeking knowledge of man's mind in God, and recognizing God as the source of all truth, must recognize him as the regulator of all good. So that metaphysics must essentially work for the good of the human race, whose preservation depends on the universal belief in a provident divinity

(Vico 1972) p. 70

LINK to the Introduction to A Whirld of Words: A Reader’s Commonplace Dictionary.

Thank you for your support.

Please RESTACK this Post and RECOMMEND A Worlde of Wordes.

SUBSCRIBE to receive daily Posts.

Enjoy!

WORKS CITED

Aeschylus, et al. (1990), Plays (Great Books of the Western World, 4; Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica) xii, 905.

Barnes, Timothy David (1981), Constantine and Eusebius (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press) vi, 458.

Bowman, Alan K. and Woolf, Greg (1994), Literacy and Power in the Ancient World (New York: Cambridge University Press) ix, 249.

Cameron, Alan (2011), The Last Pagans of Rome (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press) x, 878.

Cheng, François and Seaton, Jerome P. (1982), Chinese Poetic Writing (Bloomington: Indiana University Press) xiv, 225 p., 8 p. of pl.

Epictetus (1990), The Discourses of Epictetus (Great Books of the Western World, 11; Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica) 93-231.

Gibbon, Edward (1983), The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Vol. 1, 3 vols. (New York: Modern Library) viii, 956.

Hammond, N. G. L. and Scullard, H. H. (1970), The Oxford Classical Dictionary (2d edn.; Oxford: Clarendon Press) xxii, 1176.

Hooker, J. T. (1990), Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet (Berkeley: University of California Press) 384.

Keightley, David N. (1978), Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley: University of California Press) xvii, 281, 15 l. of pl.

--- (2000), The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China, ca. 1200-1045 B.C. (Berkeley: University of California) xiv, 209.

Kermode, Frank (1979), The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) xii, 169.

Laozi (1958), The Way and Its Power: A Study of the Tao Tê Ching and Its Place in Chinese Thought, trans. Arthur Waley (New York: Grove Press) 262.

Löwith, Karl (1949), Meaning in History: The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History (Chicago: Univiversity of Chicago Press) ix, 257.

Molnar, Michael R. (1999), The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press) xvi, 187.

Plato (1990), The Dialogues; The Seventh Letter (Great Books of the Western World, 6; Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica) viii, 814.

Plutarch (1992), Essays (New York: Penguin Books) 430.

Rutgers, Leonard Victor (1998), The Use of Sacred Books in the Ancient World (Leuven: Peeters) 316.

Shi, Jing and Waley, Arthur (1960), The Book of Songs (New York: Grove Press) 358.

Suetonius (2007), The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves and J.B. Rives (Revised edn.; New York: Penguin) xli, 398.

Thompson, Laurence G. (1989), Chinese Religion: An Introduction (4th edn.; Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth) xix, 184, 2 p. of pl.

Vico, Giambattista (1972), The New Science of Giambattista Vico (1744), trans. Thomas Goddard Bergin and Max Harold Fisch (Ithaca: Cornell University Press) xv, 398, [2] l. of pl. (1 folded).