Excerpted from A Whirld of Words: A Reader's Commonplace Dictionary. Find the LINK to the Introduction and WORKS CITED below.

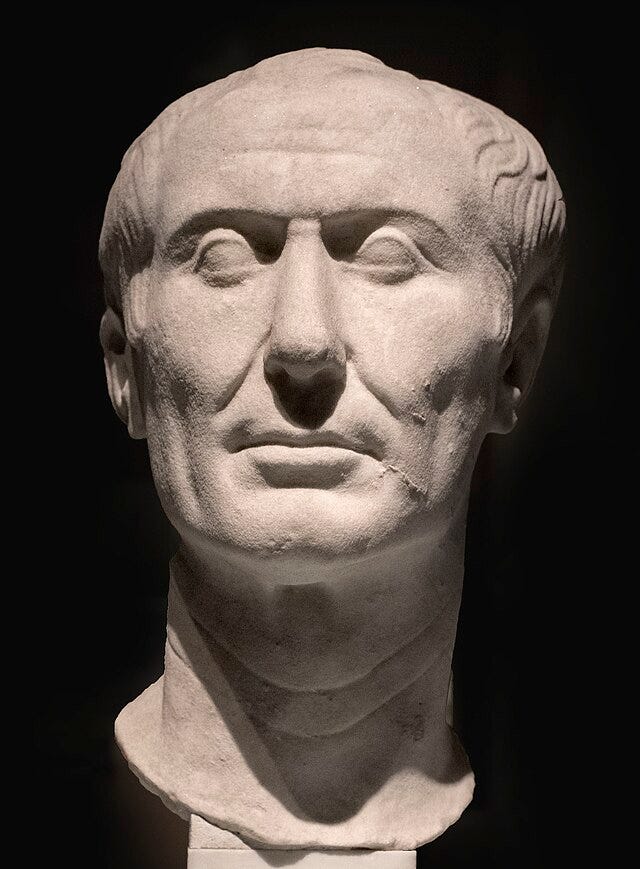

Julius Caesar

at that time some wished to gratify Caesar by voting him one honor after another, while others treacherously included extravagant honors, and published them, so that he might become an object of envy and suspicion to all. Something took place which especially stirred the conspirators against him. There was a golden statue of him which had been erected on the Rostra by vote of the people. A diadem appeared on it, encircling the head, whereupon the Romans became very suspicious, supposing that it was a symbol of servitude. Two of the tribunes, Lucius and Gaius, came up and ordered one of their subordinates to climb up, take it down, and throw it away. When Caesar discovered what had happened, he convened the senate in the temple of Concordia and arraigned the tribunes, asserting that they themselves secretly placed the diadem on the statue, so that they might have a chance to insult him openly and thus get credit for doing a brave deed by dishonoring the statue, caring nothing either for him or for the senate. He continued that their action was one which indicated a more serious resolution and plot: if somehow they might slander him to the people as a seeker after unconstitutional power, and thus (themselves stirring up an insurrection) to slay him. After this address, with the concurrence of the senate he banished them. Then the people clamored that he become king and they shouted that there should be no longer any delay in crowning him as such, for Fortune had already crowned him. But Caesar declared that although he would grant the people everything because of their good will toward him, he would never allow this step; and he asked their indulgence for contradicting their wishes in preserving the old form of government, saying that he preferred to hold the office of consul in accordance with the law to being king illegally. Later, in the course of the winter, a festival was held in Rome, called Lupercalia, in which old and young men together take part in a procession, naked except for a girdle, and anointed, railing at those whom they meet and striking them with pieces of goat’s hide. When this festival came on Marcus Antonius was chosen director. He proceeded through the Forum, as was the custom, and the rest of the throng followed him. Caesar was sitting in a golden chair on the Rostra, wearing a purple toga. At first Licinius advanced toward him carrying a laurel wreath, though inside it a diadem was plainly visible. He mounted up, pushed up by his colleagues (for the place from which Caesar was accustomed to address the assembly was high), and set the diadem down before Caesar’s feet. Amid the cheers of the crowd he placed it on Caesar’s head. Thereupon Caesar called Lepidus, the master of horse, to ward him off, but Lepidus hesitated. In the meanwhile Cassius Longinus, one of the conspirators, pretending to be really well disposed towards Caesar so that he might the more readily escape suspicion, hurriedly removed the diadem and placed it in Caesar’s lap. Publius Casca was also with him. While Caesar kept rejecting it, and among the shouts of the people, Antonius suddenly rushed up, naked and anointed, just as he was in the procession, and placed it on his head. But Caesar snatched it off, and threw it into the crowd. Those who were standing at some distance applauded this action, but those who were near at hand clamored that he should accept it and not repel the people’s favor. There were many who were quite willing that Caesar be made king openly. All sorts of talk began to go through the crowd. When Antonius crowned Caesar a second time, the people shouted in chorus, ‘Hail King’; but Caesar still refusing the crown, ordered it to be taken to the temple of Capitoline Jupiter, saying that it was more appropriate there. Of all the occurrences of that time this was not the least influential in hastening the action of the conspirators, for it proved to their very eyes the truth of the suspicions they entertained

(Nicolaus and Hall 1923) p. 33, 35, 37, 39

Divus Julius. Bibulus, Caesar’s colleague in the consulship, described him in an edict as ‘the Queen of Bithynia, who once wanted to sleep with a monarch, but now wants to be one’. The elder Curio refers to him in a speech as ‘every woman’s husband and every man’s wife’. Marcus Brutus’ mother Servilia was the woman whom Caesar loved best, and in his first consulship he bought her a pearl worth 6 million sesterces. Servilia, you see, was also suspected at the time of having prostituted her daughter Tertia to Caesar. Religious scruples never deterred him for a moment. Caesar did not utter a sound after Casca’s blow had drawn a groan from him, though some say that when he saw Marcus Brutus about to deliver a blow he reproached him in Greek with ‘You too, my son?’ [The story of Brutus’ paternity cannot be true: he was born probably in 85 BC, when Caesar was only fifteen, and long before he began his affair with Servilia]

(Suetonius 2007) p. 23, 24, 25, 28, 39, 352

Suetonius (Caesar, 49) reports Caesar’s homosexual relations with Nicomedes, the conquered King of Bithynia, and that he was called ‘The Queen of Bithynia’ for it

John Ciardi (Dante 1961) p. 271

Cato was wont to say of Caesar that he was the first sober man who had set out to ruin his country

(Montaigne 1958) p. 552

This was the noblest Roman of them all:

All the conspirators save only he

Did that they did in envy of great Caesar;

He only, in a general honest thought

And common good to all, made one of them.

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mix'd in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world 'This was a man!'

Antony (Shakespeare 1990) p. 596

the greatest man that ever lived was Julius Caesar

Alexander Hamilton (Adams and Rush 1966) p. 2

Caesar’s actions were more revolutionary than his intentions. Caesar fell, but the party, the methods, and the system prevailed in the end. A military monarchy, albeit with an aristocratic and traditionalist colouring, was substituted for an oligarchy deriving from popular election

(Syme 1979) p. 164, 167

Caesar ‒ a kind of magnificent failure

(Syme 1991) p. 127

Subscription to A Worlde of Wordes is FREE.

LINK to the Introduction to A Whirld of Words: A Reader's Commonplace Dictionary.

WORKS CITED

Adams, John and Rush, Benjamin (1966), The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush, 1805-1813 (San Marino, Calif.: The Huntington Library) viii, 301.

Dante (1961), The Purgatorio, trans. John Ciardi (New York: New American Library) 350.

Montaigne, Michel de (1958), Complete Essays, trans. Donald Murdoch Frame (Stanford University Press) xxiii, 883.

Nicolaus and Hall, Clayton Morris (1923), Nicolaus of Damascus' Life of Augustus: A Historical Commentary Embodying a Translation (Menasha, Wis.: George Banta Publishing) 2 l., 98.

Shakespeare, William (1990), Julius Caesar (Great Books of the Western World, 24; Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica) 568-96.

Suetonius (2007), The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves and J.B. Rives (Revised edn.; New York: Penguin) xli, 398.

Syme, Ronald (1979), Roman Papers: Vol. 1 (New York: Clarendon Press) xiii, [2 maps], 476.

--- (1991), Roman Papers: Vol. 6 (New York: Clarendon Press) xiv, 472.