Excerpted from A Whirld of Words: A Reader's Commonplace Dictionary. Find the LINK to the Introduction and WORKS CITED below.

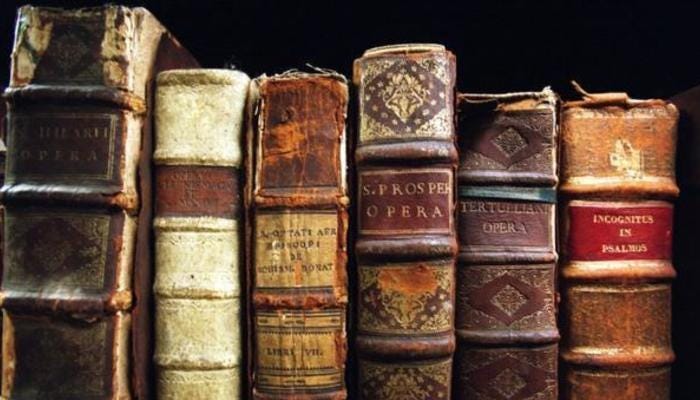

codex, pl. codices

a collection of sheets of any material, folded double and fastened together at the back or spine, and usually protected by covers; it was developed from the wooden writing tablet

(Roberts and Skeat 1983) p. 1

a codex or leaf book was not recognized in antiquity as a proper book. It was regarded as a mere notebook, and its associations were strictly private and utilitarian. The humble origin of the codex is enshrined in its name: the Latin caudex means 'a block of wood' and referred to a wooden tablet used for writing (among the Greeks such a tablet was called a deltos or pinax). From an early time it was customary to link two or more of these together by passing a string or thongs through holes along one edge, thus constructing a series of loose leaves of wood. The proper Latin name for such a collection of wooden tablets was codex

(Gamble 1995) p. 49

the first mention of literary works being published in parchment codices is found in Martial, in a number of poems written during the years 84-6. He emphasizes their compactness, their handiness for the traveler, and tells the reader the name of the shop where such novelties can be bought

(Reynolds and Wilson 1991) p. 34

at the end of the first century A.D., a great revolution took place in the manufacturing of books: the papyrus roll was gradually replaced by the codex with parchment leaves

(Weitzmann 1959) p. 2

originating in the first century, the codex (from caudex, the Latin word for tree bark) is a book composed of folded sheets sewn along one edge

(M. Brown 1994) p. 42

for the first century, codices account for virtually zero percent of surviving books. Codices make up about 5 percent of books assigned to the second century, about 24 percent of books assigned to the third century, about 79 percent of books assigned to the fourth century, and about 96 percent of books assigned to the fifth century. The major shift seems to have occurred over the course of the third and fourth centuries, the same period when many Christians transitioned from being members of a persecuted minority to positions of political power in the Roman Empire. Although we will encounter a few Christian rolls in the following pages, ‘the book’ in the early Christian centuries was almost always the codex

(Nongbri 2018) p. 22

most of the codices considered to be the earliest extant books were constructed from papyrus. Parchment codices became more popular in the fourth century and came to be much more common than papyrus codices in the fifth century and beyond

(Nongbri 2018) p. 26

a sheet, also called a bifolium (plural bifolia), is the basic unit of a codex. When folded, it forms two leaves. A leaf, also called a folium (plural folia), is one half of a sheet. It has two sides, each of which is a page. A page is one face of a leaf. When a codex lies open, the page on the left is called the verso, and the page on the right is called the recto

(Nongbri 2018) p. 26

the usual form of book in late antiquity and in the middle ages was the codex, which consisted of simple sheets of papyrus or parchment folded once and sewn together to form quires or gatherings; in origin it was an imitation of wax tablet diptychs and it had a predecessor in the parchment notebook. Martial is the first writer to mention a parchment codex format for a literary work

(Bischoff 1990) p. 20

the codex dictated a totally different way of reading a text

(Cavallo et al. 1999) p. 88

when the Christian Bible first emerges into history the books of which it was composed are always written on papyrus and are always in codex form; so universal is the Christian use of the codex in the second century that its introduction must date well before A.D. 100; the Christian adoption of the codex seems to have been instant and universal

(Roberts and Skeat 1983) p. 42, 45

A riddle in the Exeter Book speaks in behalf of an ancient codex, evidently a Bible:

One of my enemies robbed me of life,

took away my world-strength; he wet me then,

dipped me in water, then took me off

and set me in sunlight. There I lost

my hairy covering. Hard upon me

cut the knife’s edge; finely ground.

Fingers folded me, and the joy of a bird*

sped over me, sprinkling useful drops.

It dipped over the dark brim, drank of the ink,

of the wood-dye, then made its way

o’er me with dark tracks. Men enwrapped me

in protecting boards, clothed me in leather

adorned with gold. There glowed upon me

the smith’s handiwork, wondrously wrought.

Now may the ornaments and the red ink

and my glorious binding honour far and wide

the Protector of peoples, and teach no errors.

If the children of men will only choose me

they will be the sounder, stronger in triumph,

with heart bolder, thought blither

and mind wiser. They will have friends the more,

dearer and closer, more true and clinging,

trusty and good, who will give them wealth

and great glory, and with gracious deeds

will fold them round and fast hold them

in their embrace. Guess what I am

to man in his need. My name is mighty,

to heroes a grace; and I am holy.

* The ‘joy of a bird’ is a feather; here used as a kenning for the pen that wrote the manuscript.

(Williams 1940) p. 15

tables of chapter headings, alphabetical tables by subject and running heads became standard features of the scholastic codex

(Cavallo et al. 1999) p. 134

the codex became the vehicle for a new kind of narrative, reflecting new views on the divine and human arrangement of time

(Kermode 1979) p. 89

the early codex probably came to prevail for the same reasons the book abides: price, portability, and random access

[JS]

codicology

systematic inventorization of the texts in manuscripts; archaeological investigation of how books were put together, decorated, and bound

(Ullman and Brown 1980) p. xii

the study of the physical manufacture of the book

(M. Brown 1990)

turning to the evidence of Hebrew codicology, one finds an almost total absence of Hebrew manuscripts between the second and the ninth centuries

(McKitterick 1990) p. 146

Codex Amiatinus

Cassiodorus had assembled a text of Jerome's version of the Scriptures into nine volumes completely revised by himself. This text seems to have been preserved in the first and oldest quaternion of the best manuscript of the Vulgate, the Codex Amiatinus, which was written at Jarrow (perhaps under the direction of Bede), temporarily lost sight of in 716 after the death of abbot Ceolfrid (who was taking it to the pope at Rome), and rediscovered at the monastery of Monte Amiata in southern Tuscany, whence it passed into the Laurentian Library at Florence. The frontispiece of the Codex Amiatinus represents the prophet Ezra correcting the Scriptures, seated before a press containing the nine volumes mentioned above

(Cassiodorus 1946) p. 33

in the famous Codex Amiatinus produced at Bede’s monastery is a diagram which has been variously described as the Tabernacle and the Temple. The huge manuscript, a pandect or single-volume copy of the whole Bible, is the survivor of three such copies made for the joint foundation of Wearmouth-Jarrow under the direction of Ceolfrith, during his abbacy from 688-716, and was the copy which Ceolfrith eventually, in 716, took with him on his final pilgrimage to Rome to present to the pope. The book’s format and illustrations have often been seen as modeled on another pandect, the now lost Codex Grandior produced in the monastery of Cassiodorus (d. 598) at Vivarium in Italy, which has usually been identified with the pandect ‘of the old translation’ brought back to Northumbria from Rome in 678, a year or two before Bede’s admission to the monastery as a child of seven. The whole enterprise of producing the Codex Amiatinus and its two sister pandects, in Roman uncial script and from the best available manuscripts, based not on the Old Latin translation but on ‘the Hebrew and Greek originals by the translations of Jerome’ (including his third revision of the Psalms, iuxta hebraicos), was an astounding feat of scholarship and scribal activity

(Bede and O'Reilly 1995) p. lii, liv

a manuscript produced between 688 and 716 at Wearmouth – the Codex Amiatinus, now in the Bibliotheca Laurenziana in Florence, and named from Monte Amiato, where it came to rest in the Middle Ages. It was only one of three large copies of the entire Bible, called a pandect (an all-inclusive volume), that were produced at this time in Wearmouth. It was based on an Italian original – the Codex Grandior, 'The Larger Codex', which had been prepared at Vivarium by Cassiodorus himself. This Grand Codex arrived at Wearmouth when Bede was a boy

(P. Brown 2003) p. 357

Bible

complete Greek Bibles were a rarity in antiquity (only four survive). The four Greek Bibles that scholars presume were at one time ‘complete’ (meaning that they are suspected to have contained some form of what are now commonly called the Old and New Testaments) are the Codex Sinaiticus, the Codex Vaticanus (LDAB [Leuven Database of Ancient Books] 3479), the Codex Alexandrinus (LDAB 3481), and the Codex Syri Rescriptus (LDAB 2930)

(Nongbri 2018) p. 26

book

the terms 'liber', 'volumen', and 'tomus', originally used to designate the papyrus roll, were transferred to the codex after it had become the almost exclusive form of book

(Bischoff 1990) p. 20

the parchment codex, or 'book' as it came to be called in English (a derivative of Germanic bōkā or 'beech', after the earliest material of rune tablets

(Fischer 2003) p. 84

of the nearly 3,000 Greek papyrus and parchment books that have been recovered from Egypt and are datable to the first five centuries of our era, about eighty percent are in roll format, and twenty percent are codices; whereas for classical literature the roll was practically the only book format in use until the third century, and the roll continued to be the dominant format for this literature until the fourth century, for Christian literature, by contrast, the codex was from the beginning practically the only book format in use: Christian books in roll format are scarcely known

(Van Kampen and Sharpe 1998) p. 37

bookselling

codex. The first mention of literary works being published in parchment codices is found in Martial, in a number of poems written during the years 84-86. He emphasizes their compactness, their handiness for the traveler, and tells the reader the name of the bookseller, Secundus, and the location of his bookshop in Rome where such novelties can be purchased

[JS]

Cassiodorus

Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus (c. 485-580) was an editor and promoter of the Vulgate text. Cassiodorus was a late Roman senator who in his mid-fifties retired from the civil service and founded a monastery on his family estate near Naples. It was called the Vivarium ('fish pond'), named after the water gardens in the grounds. He furnished the monastery with three complete sets of the books of the Latin Bible. The first set comprised the Bible arranged into a set of nine matching volumes. Presumably these followed the standard Vulgate text. The second he calls his Codex Grandior, the 'larger codex'. The third book was a one volume Bible, presumably the Vulgate again, in small script. The manuscripts made for Cassiodorus seem to have been acquired by an Englishman visiting Rome in the seventh century, Benedict Biscop (d. 690), who then brought them back to Northumbria in the very north of England. The Codex Grandior was evidently especially admired there. According to a contemporary biography of Ceolfrith (d. 716), abbot of Wearmouth and Jarrow, three vast manuscripts were made on the same model, one each for Ceolfrith's two monasteries and one intended for the pope. Their text was copied according to the final Vulgate text of Jerome. Ceolfrith himself set off in June 716 to carry the pope's copy to Italy, but he died on the journey. The manuscript survives. It is known as the Codex Amiatinus, one of the purest and best copies of Jerome's Vulgate. From the sixteenth century onwards it has been accepted and used as the most reliable manuscript for editors of Jerome's translation. It is a complete Bible, or 'pandect'. The word is from the Greek, pan (all) and dekhesthai (to receive), and a pandect is an all-inclusive Bible, or a complete text of every book combined into a single comprehensive volume

(De Hamel 2001) p. 32

Jerome

te Bethlehem celebrat, te totus personat orbis (‘Bethlehem praises you, the whole world proclaims you’) runs the caption for Jerome’s portrait in the library of Isidore of Seville, which was later repeated verbatim in the preliminaries of the Codex Amiatinus. The first hemistich surely echoes the well-known epitaph of Virgil (Mantua me genuit...), gratuitously but purposefully quoted by Jerome in the Chronicle

(Vessey 2009) p. 232

the Echternach Gospel Book, perhaps made in Lindisfarne, north of Jarrow, has a curious subscription claiming that it was corrected against a codex which had belonged to Jerome himself and which was in the year 558 in the library of the priest Eugipus. This priest has been tentatively identified as a man recorded as abbot of a monastery near Naples

(De Hamel 2001) p. 34

manuscripts

there are approximately 172 biblical manuscripts or fragments of manuscripts written before A.D. 404 or not long thereafter; of these 172 items, 98 come from the Old Testament and 74 from the New; 158 texts come from codices and only 14 from rolls; eleven, without exception Christian, may be assigned to the second century and are thus the earliest Christian manuscripts in existence; all are on papyrus and in codex form

(Roberts and Skeat 1983) p. 38, 40, 42

the earliest extant Gospel manuscript, the Rylands St. John (P 52) probably never contained more than that Gospel, as certainly was the case with the somewhat later Bodmer St. John (P 66) and the third-century P 5, a bifolium consisting of conjoint leaves from the beginning and end of a single-quire codex of the same Gospel

(Roberts and Skeat 1983) p. 65

membranae

parchment exercise-books in codex form

(Bonner 1977) p. 129

nature

Natura Codex est Dei

St. Bernard (Willey 1940) p. 42

nomina sacra

the significant fact is that the introduction of the nomina sacra seems to parallel very closely the adoption of the papyrus codex; and it is remarkable that this development should have taken place at about the same time as the great outburst of critical activity among Jewish scholars which led to the standardization of the text of the Hebrew Bible

T.C. Skeat (Roberts 1979) p. 41

palimpsest

a parchment from which the original writing has been erased (but is still faintly visible) in order to write on it a second time; also known as codex rescriptus

(Glaister 1960) p. 293

pandect

the words ‘in the pandect’ translate Bede’s phrase in pandecte. The nominative form pandectes, is a transliteration of the Greek πανδεκτης (lit. ‘an all-receiver’, from παν = ‘all’ + δεχομαι = ‘I receive’). It was ‘a book containing everything’, a sort of encyclopaedia, and in Christian parlance it was used to denote the Bible, just as the word bibliotheca, ‘a library’ or ‘collection of books’, was used by St Jerome. Here it means Cassiodorus’s complete and therefore large (hence Codex Grandior) copy of the entire Latin bible [sic], now lost, which apparently Ceolfrith brought back from Rome to Wearmouth/Jarrow and Bede saw with his own eyes. So there were close links between it and the well-known Codex Amiatinus now in the Laurentian Library in Florence, a copy of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (i.e. popular) version which was made at Wearmouth/Jarrow and was being carried to the Pope in Rome by Abbot Ceolfrith when he died in northern Italy

(Bede and O'Reilly 1995) p. 66

paper

paper became an alternative to papyrus about the end of the eighth century, since the Arabs are believed to have learned the technique of manufacture from some Chinese prisoners of war taken after a battle at Samarkand. The oldest Greek book written on paper that is now extant is a famous codex in the Vatican Library (Vat. gr. 2200), usually dated c. 800. It is famous because of its eccentric script

(Wilson 1983) p. 63

Vulgate

the Latin version of the Bible as translated by St. Jerome c. 380-405; of surviving manuscript copies the Codex Amiatinus is perhaps the most important

(Glaister 1960) p. 432

the earliest surviving complete Vulgate Bible, the Codex Amiatinus, made at Wearmouth-Jarrow, was completed in the early years of the eighth century, before 716, under the direction of Abbot Ceolfrith, and is now in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence

(Van Kampen and Sharpe 1998) p. 151

world

the world is our beloved codex. We do, living as reading, like to think of it as a place where we can travel back and forth at will, divining congruences, conjunctions, opposites; an appropriate algebra. This is the way we satisfy ourselves with explanations of the unfollowable world – as if it were a structured narrative

(Kermode 1979) p. 145

Subscription to A Worlde of Wordes is FREE.

LINK to the Introduction to A Whirld of Words: A Reader's Commonplace Dictionary.

WORKS CITED

Bede and O'Reilly, Jennifer (1995), Bede: On the Temple, trans. Seán Connolly (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press) lv, 142.

Bischoff, Bernhard (1990), Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages (New York: Cambridge University Press) xi, 291, 50 p. of pl.

Bonner, Stanley Frederick (1977), Education in Ancient Rome: From the Elder Cato to the Younger Pliny (Berkeley: University of California Press) xii, 404.

Brown, Michelle (1990), A Guide to Western Historical Scripts: From Antiquity to 1600 (London: British Library) 138.

--- (1994), Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms (Malibu, Calif.: J. Paul Getty Museum) 127.

Brown, Peter (2003), The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200-1000 (2nd edn.; Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers) viii, 625.

Cassiodorus (1946), An Introduction to Divine and Human Readings (New York: Columbia University Press) xvii, 233.

Cavallo, Guglielmo, Chartier, Roger, and Cochrane, Lydia G. (1999), A History of Reading in the West (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press) viii, 478.

De Hamel, Christopher (2001), The Book: A History of the Bible (New York: Phaidon) 352.

Fischer, Steven R. (2003), A History of Reading (London: Reaktion) 384.

Gamble, Harry Y. (1995), Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts (New Haven: Yale University Press) xii, 337.

Glaister, Geoffrey Ashall (1960), An Encyclopedia of the Book: Terms used in Paper-Making, Printing, Bookbinding and Publishing (Cleveland: World) 484.

Kermode, Frank (1979), The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) xii, 169.

McKitterick, Rosamond (1990), The Uses of Literacy in Early Mediaeval Europe (New York: Cambridge University Press) xvi, 345.

Nongbri, Brent (2018), God's Library: The Archaeology of the Earliest Christian Manuscripts (New Haven: Yale University Press) xii, 403.

Reynolds, L. D. and Wilson, Nigel Guy (1991), Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (3rd edn.; New York: Oxford University Press) ix, 321, 16 p. of pl.

Roberts, Colin H. (1979), Manuscript, Society, and Belief in Early Christian Egypt (The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 1977; New York: Oxford University Press) 88 [1].

Roberts, Colin H. and Skeat, T. C. (1983), The Birth of the Codex (London: Oxford University Press) 78, 6 p. of pl.

Ullman, B. L. and Brown, T. Julian (1980), Ancient Writing and Its Influence (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) xviii, 240, 16 p. of pl.

Van Kampen, Kimberly and Sharpe, John L. (1998), The Bible as Book: The Manuscript Tradition (London: Oak Knoll Press) xi, 260, 16 p. of pl.

Vessey, Mark (2009), 'Jerome and the Jeromanesque', in Andrew Cain and Josef Lössl (eds.), Jerome of Stridon: His Life, Writings and Legacy (Burlington, VT: Ashgate), 225-35.

Weitzmann, Kurt (1959), Ancient Book Illumination (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) xiv, 166.

Willey, Basil (1940), The Eighteenth Century Background: Studies on the Idea of Nature in the Thought of the Period (London: Chatto and Windus) viii, 301, 1 l.

Williams, Margaret (1940), Word-Hoard: Passages from Old English Literature from the Sixth to the Eleventh Centuries (New York: Sheed & Ward) xvi, 459.

Wilson, Nigel Guy (1983), Scholars of Byzantium (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press) vii, 283.

Ah! Something I know a lot about–great set of resources here! The Nongbri book is a solid introduction to early codicies. Additionally, for more on the development of nomina sacra (and various theories—scholars have still not reached a consensus) see Hurtado, Larry. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. (Grand Rapids: William B. Ehrdman's Publishing Co.) 2006, p 95–135. This is a chapter summarizing theories on the origin of nomina sacra and proposing his own theory.